The United States has the strongest protections for free speech of any country in the world, and with that comes distasteful speech. It’s up to us to counter that bad speech with good speech, constitutional law experts said at a campus forum last week.

“Part of the reason we protect speech as aggressively as we do is that we trust ourselves,” said Alan Brownstein, a professor in the School of Law. “We trust the people to challenge evil messages, and we'd rather have the people doing that than the government doing that.”

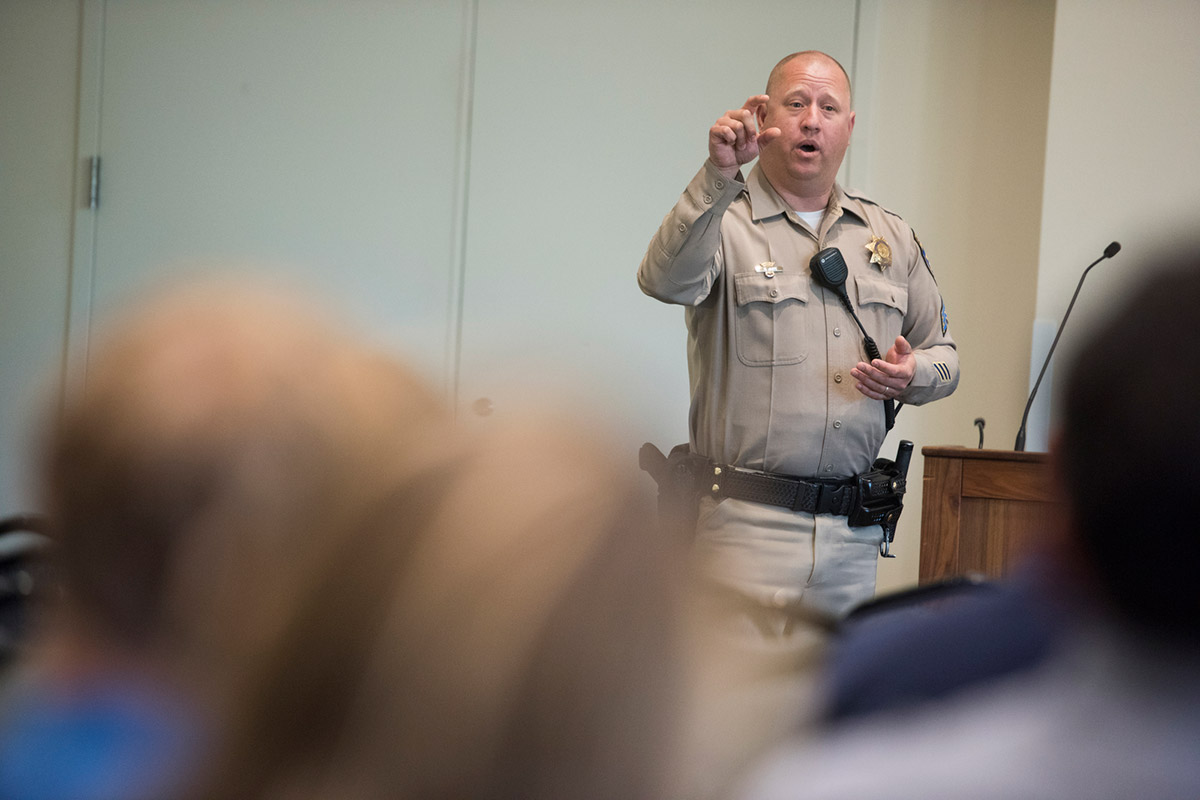

He and other free speech experts — law professors and a CHP sergeant who issues permits to protestors and event organizers at the state Capitol — described what protections the First Amendment does and does not provide during a forum on campus last week.

The panel discussion, the third in the campus’s Dialogue and Discernment series, was titled “Hate Speech, Free Speech, More Speech or Less Speech: The Quad as Free Expression Zone or Safe Space?”

The legal experts stressed that if any restrictions are made on free speech, they can only be “time and manner” restrictions — say, a ban on the late-night use of bullhorns in residential neighborhoods, but not on what can be said through those bullhorns.

That sets the United States apart, they said.

“Canada, Australia, most western European countries — obviously democracies — they prohibit hate speech,” Brownstein said. “We do not.”

Asked about protests over the recently canceled appearance by Ann Coulter at UC Berkeley and the canceled Milo Yiannopoulos event at UC Davis, they said the First Amendment covers speech, but not actions.

“Conduct is not speech,” Brownstein said. “Obstructing access to a room or a business or an activity is not protected speech.”

And as for the content at events like those, he said the First Amendment doesn’t protect people who make threats or incite violence — but hate speech is fair game, no matter how vile.

Trying to stifle someone with vile views usually makes them a “First Amendment martyr” and greatly amplifies their reach, Brownstein said.

But, Interim Chancellor Ralph J. Hexter asked from the audience, what about federal protections against creating a hostile work or learning environment?

While employers can be held liable for allowing so much offensive speech it prevents people from doing their jobs, it’s much harder to make the case that offensive ideas limit an educational experience, because that’s central to what it means to attend a university, Brownstein replied.

That exchange of ideas is vital, even when some of the ideas are incredibly offensive, the panelists said, noting that when a fringe group is prevented from speaking, everyone loses out.

“In some ways you might say the harm isn't even necessarily to the group that's excluded,” Larson said. “The harm is to everybody else that was deprived of the normal functioning marketplace of ideas that you would expect to have.”

Moderator Madhavi Sunder, senior associate dean and professor in the School of Law, noted a theme running through the forum, comparable to the experience of every first-year law student: Professors pointing out that in the end, most things are a bit of a gray area.

“The professor always says it's a hard question and there are no bright-line answers,” she said.