Woody vegetation, such as trees and shrubs, has increased dramatically in Ozark grasslands over the past 75 years, according to a study published this week in the journal Landscape Ecology.

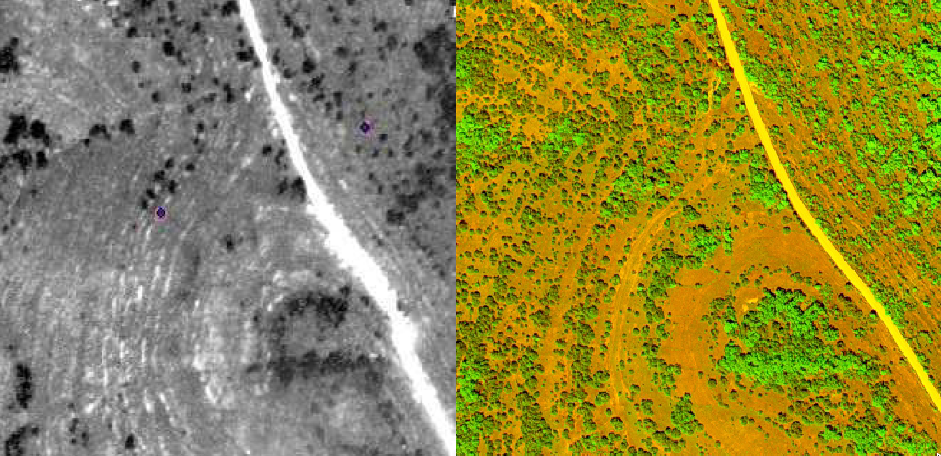

The study examines grasslands called dolomite glades in the Mark Twain National Forest near Ava, Missouri. It analyzed historical aerial photos and found that woody vegetation cover increased from 8 percent in 1939 to 59 percent in 2014.

Fire was largely absent from this landscape between 1939 and 1984 and then was reintroduced within the past 30 years. The study shows that while prescribed fire has helped “hold the line” against woody encroachment, it has not been able to reverse it. It added that the chances of reversing it are unlikely once woody plants cover more than 40 percent of the landscape. Meanwhile, unburned grassland areas have largely become densely wooded.

The future of grasslands

The study area is characteristic of a range of grassland and savanna ecosystems, and the findings raise questions about the future of grasslands: if, despite intensive management efforts, these ecosystems continue to favor woody vegetation, will it be possible to maintain open grasslands for the foreseeable future?

Grasslands represent a major component of biodiversity in the Ozarks. Most plants and animals in these habitats need open grasslands and won’t tolerate dense areas of trees and shrubs.

Prescribed fire ‘essential’

“We show that prescribed fire is essential to the continued existence of these grasslands,” said lead author Jesse Miller, who completed the research as a Ph.D. student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis. “Fire was largely removed from the landscape for several decades. Now we better understand the ecological importance of fire for grasslands, and we’re still trying to reverse changes to grasslands that occurred during the period of fire exclusion.”

The study said that successful restorations require vigilant monitoring and management. The authors suggest that grassland restoration should not remove all woody plants, as some species, such as oaks, have been present historically. When possible, managers should prioritize maintaining existing grassland habitat and intervening before woody vegetation becomes so dense that it requires mechanical removal.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Jesse Miller, UC Davis, jedmiller@ucdavis.edu