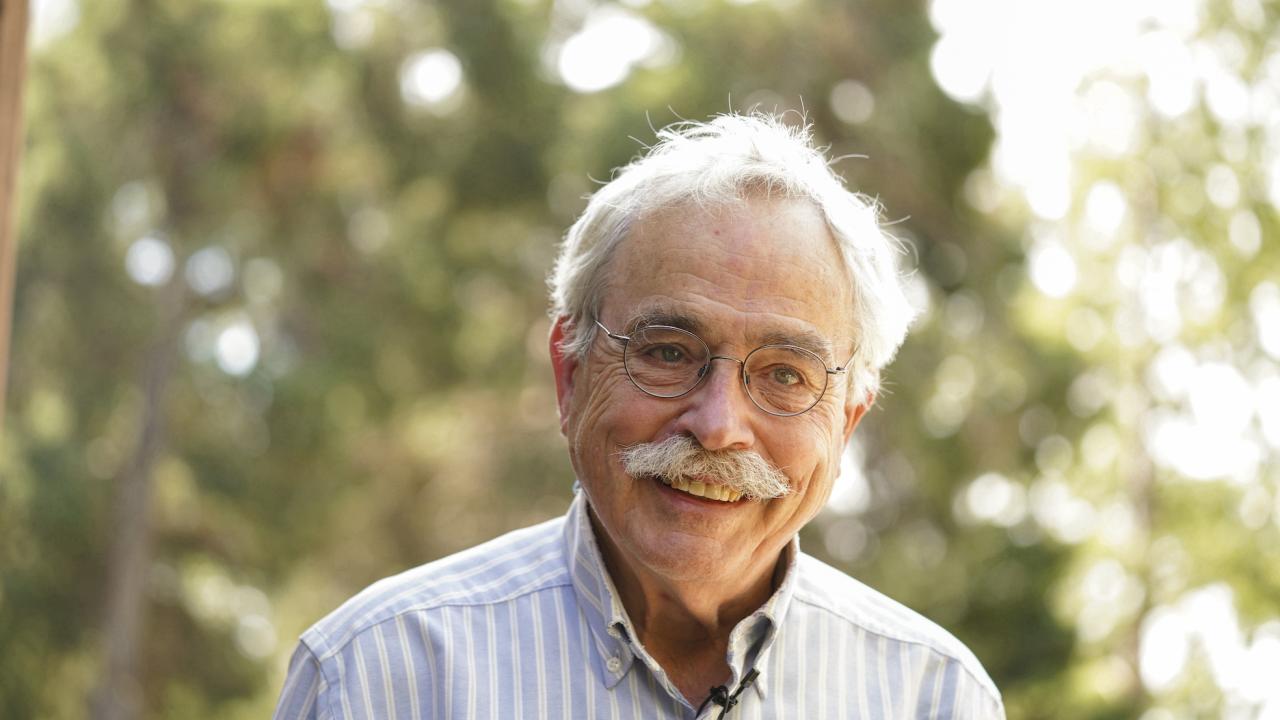

Peter Moyle is widely considered the “godfather of California fish biology.” The UC Davis professor emeritus has been conducting native fish surveys here for more than 50 years. He also played a major role in restoring Yolo County’s beloved local stream, Putah Creek.

This article is part 1 of the series “Confronting Climate Anxiety”

View all eight parts of the series, and find out what scientists are doing to turn climate anxiety into climate action.

His work sounded alarm bells about native fish, including the endangered Delta smelt — a nearly extinct icon of California’s water woes. Unfortunately, the bells keep ringing: 80% of native fish have declined in the state since he first began studying them.

Despite the sad fish tales, he appears to be quite happy, with a natural glint in his eye, a resting half smile on his face and a warmth that draws both fish and people to him.

I sat with him on a warm winter day along the UC Davis Arboretum waterway to learn how he’s kept climate despair at bay while he’s continued, Lorax-style, to speak for the fish.

Fish biology

You’ve been at this for a long time. What drew you to this field?

I’ve just been interested in being outside. My dad was a fisheries biologist, my mother was an aquatic biologist, it seemed very natural. The nice thing with working with fish is it takes you to a lot of interesting places — a lot of beautiful streams and not so beautiful streams.

Climate optimism

What was the fisheries landscape like when you began, and has your outlook changed given what you’ve witnessed?

Why do I keep being so optimistic when I keep publishing papers showing how much the fish populations have changed?

I came to California in 1969. I was hired to teach fish biology at Fresno State, but I knew nothing about the local fishes. So I found students to go out with me, and we spent the next couple of summers going up and down streams flowing into the San Joaquin Valley looking for fish. Most people who studied fish in California either went to the high Sierra or the California coast, where it’s cool, but neglected the fishes in between. These in-between fishes were having the most problems because they were so neglected. I made a strategic decision to study them.

I’ve always liked working on issues where I thought I could make a difference in conservation.

Ironically, the first paper I published on California fish was documenting the loss of Chinook salmon in the San Joaquin River. At the time, I hadn’t realized that when Friant Dam was built in the 1940s, there were still 50,000 spring-run Chinook going up the river. But the salmon were just not that important to most people. The agencies said, “We can build a hatchery and do better than Mother Nature.” So the dam was built and, without water, the run died. That was the end of San Joaquin salmon.

That brings us back to that question: Why are you still so optimistic?

I had a great career studying a tragedy. I’ve been really fortunate. I love teaching. I quickly realized I could not teach if I was not doing some kind of research on native fishes. Then in 1972, I was asked by UC Davis to apply for the job here.

My wife, Marilyn, and I moved to Davis; we had a family; life was good — except that the phenomena I was studying was the long-term decline of fish. At the time, I didn’t even really understand that.

In the early 1970s, when I first started sampling the fish, about a third were in serious decline. Streams were disconnected by dams, but most places I went, I could find native fish by knowing where to look. Today about 80% are in decline, and over 30% are already listed [as threatened or endangered species].

But it’s been a good life. I’ve had so many good students. I enjoy being outside, telling people about the environment. I’ve gotten positive and some negative feedback from my involvement in lawsuits to protect the native fish. But in many small ways, I’ve done what I can to keep the native fish going.

Delta smelt decline

You’ve gotten so many students out on the water and in the marshes. Tell me about that.

Once I settled in Davis, I started finding places I could sample. Most importantly, I got involved in studying the fishes of Suisun Marsh. It was a great place to study because my students and I could have our boats in the water within an hour. I started doing monthly sampling there, funded by the Department of Water Resources, and found it was a haven for native fish. It still is. From the beginning, I took students along so they could get experience sampling fish. That work continues through the Center for Watershed Sciences.

When we first started sampling Suisun Marsh in 1979, Delta smelt were common. Then over the next few years, they basically disappeared from our samples and declined elsewhere in the Delta. I was also looking at the life history of the Delta smelt and its basic biology. So by default, I became the world’s expert on Delta smelt. I thought, “This is clearly an endangered species, and we ought to get it listed.” So I drafted the first petition for its listing myself.

Making a difference

So you’ve been working in environments you love with people you like. You take action on the problems you see where you think you can help. Did you ever feel sad when you saw these trends happening? Did you ever think: “What am I doing all this for? Nobody cares about my little fish.”

Oh, yeah. People ask me that all the time. I just say: I gotta do what I can.

For one thing, it was all really interesting. There’s a certain joy in just being out in the field and doing research you know ultimately could benefit the species. I was pretty naïve, too. I didn’t recognize how massive the water infrastructure really was and how much it dominated state water policy. That never sinks in until you’re directly involved in some of the controversies.

I've always liked working on issues where I thought I could make a difference in conservation.

Climate change is just one threat impacting fish. Has your perspective on the environment changed over the years?

The fish in California are not in serious decline because of climate change. The cause of fish declines was everything else — dam diversions, nonnative fishes, a whole complex of things.

In the past, I rarely had much concern for climate change because the effects of dams, land use and other environmental changes were immediate problems that were so severe. Climate change was something to worry about for the future, not here and now. But that’s changed. Climate change is exacerbating the other problems Californians have created for our native fishes. For example, the current drought is unprecedented in its severity, and it is drying up streams.

Dealing with eco anxiety

How do you deal with climate anxiety? Did you ever feel the need to get a break from the work?

I’ve gone to other countries to work for short periods. But the problems are the same everywhere. You can’t go to some other place and just forget about it. We have too many people on this planet — that’s the fundamental problem — and they impact the fishes everywhere in the world.

But I have so many things to keep me busy; I just don’t let it get me down. It’s just the way I am.

How do you feel when you hear about other climate-related issues? Like when the smoke comes and you see changes in California, and you hear people saying, “I don’t know if I have a future here.”

One of the papers I published recently is on reconciliation ecology. That’s the idea that you’ve got to make the best of a bad deal. Look in this area we’re in right now, the university Arboretum — there’s nothing natural about it. Except for some oaks, most of the trees are nonnative. But it provides habitat for a lot of migratory birds, which are native. The more places like this you have, the better off the biota will be.

If you use fish as an excuse, you can connect watersheds all over the state, and that protects not only the fish, but also migratory birds, brush rabbits and all kinds of other critters.

One of my favorite examples is the riparian brush rabbit. It only occurs in the San Joaquin Valley along streams. I’ve been involved in restoring the San Joaquin River. If you restore the river for fish, you restore the riparian habitat, and the endangered riparian brush rabbit will do much better.

I had a great career studying a tragedy.

Taking action

That reminds me of Putah Creek and your work restoring that stream.

Putah Creek gives people hope. It shows that you can reestablish stream flows and salmon runs and that if you use the natural flow regime, you can actually make a difference.

It helps to be in a place like Davis where there are so many people around to help out. [UC Davis ecologist] Melanie Truan is a perfect example of that. She doesn’t get much credit for what she does, but what she does is really good. Every time I see a bluebird out at Putah Creek, I think of Melanie. That bluebird would not be there if she hadn’t led the effort to get those nest boxes up there.

If a student was sitting here telling you, “I love fish, I love being outside, but it’s hard for me to see the things I love disappearing and don’t know if I can do that every day,” what do you say?

Take things one at a time. There are projects like Putah Creek around the state where local groups are trying to get streams restored. There’s even a group trying to restore the LA River — talk about optimists!

There’s an essayist, Anne Lamott, who talked about how her father was a bird watcher who knew all the birds and their songs. She asked, “Dad, how do you learn all these things?” He said, “Bird by bird.”

I think that’s the way it is with conservation, too. All of California is subject to change. If you want to keep your local habitats going, with fish and other things, you have to do it bird by bird.

Continue the series with part 2, “Levi Lewis: The Value of ‘And’”

In part 2 of the “Confronting Climate Anxiety,” series, fisheries ecologist Levi Lewis discusses climate anxiety, privilege, fish and the power of “and.”

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin is an environmental science writer on the UC Davis News and Media Relations team. 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu. Twitter @UCDavis_Kerlin.

Download photos of Peter Moyle.