Amanda Frazier studies young polar fish — species with no colder place to go as the planet warms. A Ph.D. candidate in the Graduate Group in Ecology at UC Davis, she travels to Antarctica to learn how these vulnerable fish use sea ice and how they adjust their bodies and behaviors to cope with climate change. She’s thought a lot about what humans may have to learn from them about dealing with stress.

This article is the final part of the series “Confronting Climate Anxiety”

View all eight parts of the series, and find out what scientists are doing to turn climate anxiety into climate action.

Here, Frazier describes the soft side of Antarctica, a unique way she deals with her own anxieties and holding kindness in our work and lives.

What goes through your mind when you’re researching these fish and how they deal with stress. Do you draw parallels with your own life and climate anxiety?

Yes, it makes sense to me to study stress when I can personally feel stress impacting my life. There’s an emotional aspect of studying climate change and just existing as a person in a world that’s changing.

I just read this book I really like called Getting to the Heart of Science Communication by Faith Kearns. Have you read it?

I’m actually reading it now.

Great. Her whole thesis is we have to relate to people and see them as emotional beings and embrace our own emotional selves to connect on scientific communication issues. I really see that in my own work. Climate change is such an emotional topic — from climate denial perspectives to the anxiety and grief so many people feel with climate disasters. I have to find ways to hold that while I’m working. It’s an interesting balance.

I think in western science, we frown upon people bringing in emotion. I think that’s a disservice to ourselves, to our science, to our community. It’s actually really powerful to hold space for that. Especially when you’re interested in communicating science to the public. You have to connect; you have to feel things. It won’t be successful if you follow this one-directional deficit model of, “I have to tell you things really academically, and you have to listen to me.”

On that note, I’ll share with you — perhaps not surprisingly — that I’m doing this series because I’ve been anxious and grieving climate change. It’s been great to talk with climate scientists about it. What sorts of things do you do to take care of yourself when climate anxiety sets in?

I’m going to take a tangent and then make sure to answer that. I really love this question. For me, my family actually just lost our home to wildfire in the end of December in Colorado.

Oh, Mandy, I’m so sorry.

Thank you. That experience was really pivotal for me as a human and as someone who studies climate change. I was on Twitter the day of the fire and days after because it’s excellent for emergencies and things like evacuating. Because I’m also on “academic Twitter,” I was seeing all these posts from fire scientists saying things like, “Oh, well, this is the wildland-urban interface, and that’s the problem here” — almost trying to point fingers. It was so infuriating to me to literally have the properties and homes still smoldering and have these people really remove themselves and remove the connection people have with their homes in this discourse of intellectualizing the experience. And I thought, “I never want to do that.”

That experience really emphasized to me that note of holding a gentleness and kindness in our work. I hate the notion that to be a great scientist you have to be very cutthroat or serious. No one has training in how to listen and relate to people — how to hold kindness.

Often toward the end of a dive I’m so cold, but I want to stay because it’s so beautiful that I just want to have time to explore.

So when you ask what I do to cope, that’s a major piece of it — allowing all of these emotions and intentionally trying to be kind and gentle with myself, the people I work with and the community overall. Because more and more, people we work with have evacuated for fires or had their homes burned down in a fire. Feeling these feelings and allowing space for it is productive.

More specifically, I see a lot of value in tying in things I’ve learned from social justice work. I volunteer with CARE on campus. It’s the sexual violence prevention and resources group. I bring that up because that space is so trauma-informed, and so gentle and inclusive. I see so much value in bringing those grounding principles into our work as scientists and climate-adjacent scientists.

And I really focus on the things that bring me joy, like playing with my dog, Maisie. Just taking care of a creature and having that bond with a creature is so joyful and has brought so much balance to my life. I have to walk her and feed her and play with her every day. I don’t know if you’ve seen that meme from the dog’s perspective of, “I have to take my human for her mental health walk.” I just love that.

Because, yeah, it’s really depressing: These species I study may not exist by the time I die. That’s a lot to carry and feel.

A lot of people talk about how they get out in nature to cope. I find it so interesting that you also cope with this heavy topic of climate change by going into what’s an arguably heavier topic of sexual violence. Can you talk about how helping others also helps you?

I do find it very rewarding. Often in my work, I feel like I’m not impacting anyone’s lives. I just study these tiny fish at the end of the world, and I’m going to write a paper, and no one is going to read it. Those are the grumpy days.

By volunteering with CARE and programs where I can actively talk with students and answer questions, it helps me feel like maybe we’re moving the dial a bit about sexual violence. I just felt this need to do something. It is heavy, but the big lesson is that when the space you work in and the people with whom you share that space is trauma-informed, intentionally intersectional and gentle, that space can hold everyone through those challenging feelings.

More and more, people we work with have evacuated for fires or had their homes burned down in a fire. Feeling these feelings and allowing space for it is productive.

All these students I volunteer with are so amazing. Everyone puts their hearts into this heavy topic, and the space holds us there. That’s where I’m like, “Ah, we need this in our grad groups, our institutions and our collaborations.” We need those check-ins and just celebrating the humanity of people.

Let’s go back to Antarctica for a bit. Most of us haven’t been there. What’s it like?

It’s amazing, full stop. To me, it’s the most beautiful place on Earth. It’s paradise. There’s a narrative that polar science is so badass, and you have to dominate and be this heroic explorer. I don’t like that vibe. To me, it’s so stunning and more gentle than I think people perceive it as being. I think of the poles as so vulnerable — how the ice is always breaking and moving out. I view that as softness.

The research station is facing out to McMurdo Sound. You wake up, go to the lab. The sound is completely frozen, and the Transantarctic Mountains are behind the sound. So it’s this stunning landscape of mountains and oceans.

People are like, ‘You must be so tough to go there.’ But I’m like, ‘You wear jackets!’

People are like, “You must be so tough to go there.” But I’m like, “You wear jackets!” I feel really comfortable. I love that cold feeling on your cheeks and breathing it in. Ah! I really love that. Or taking off your layers and defrosting a bit. It just brings me a lot of joy to be able to work there. I’m very lucky that I get to dive there to collect our fish.

Wow! I didn’t know that. How do you dive in Antarctica?

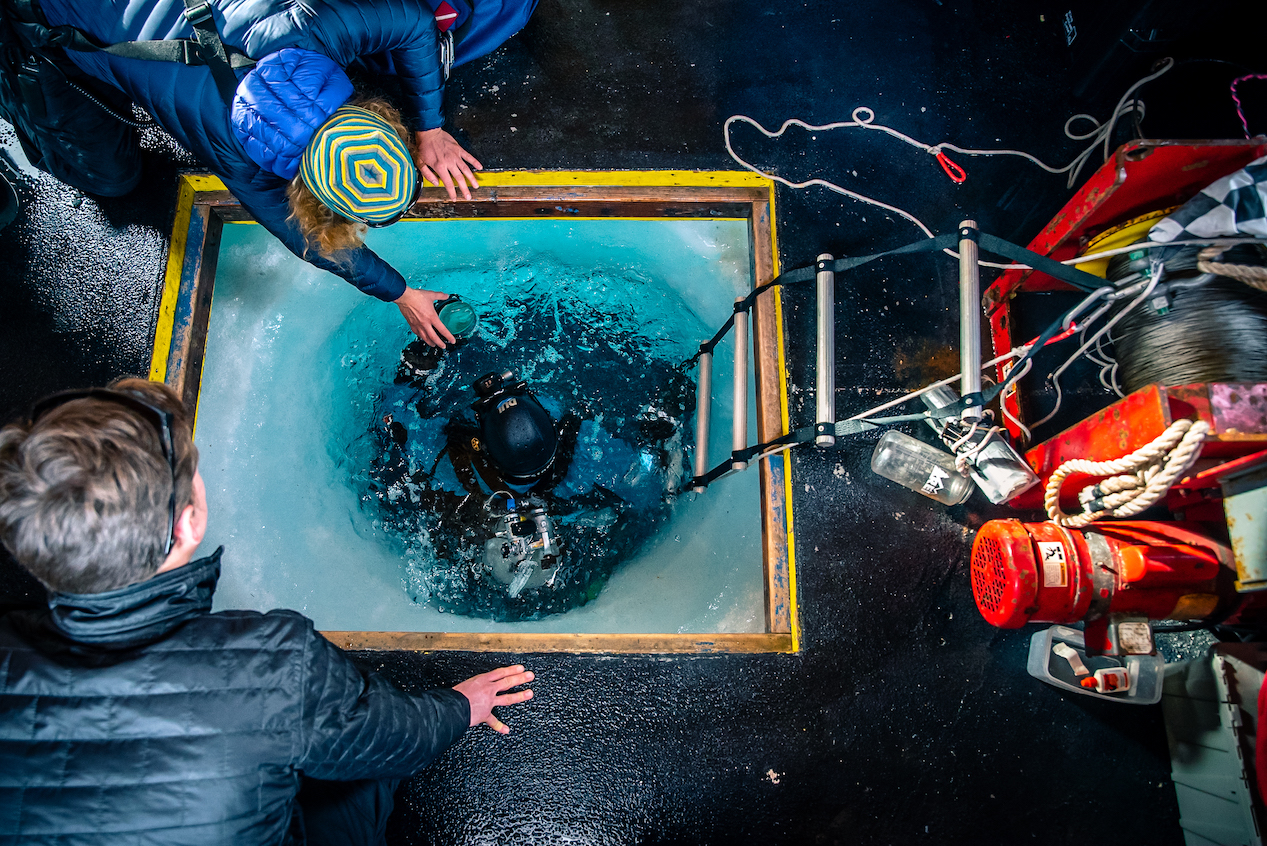

For young life stages, you have to collect the fish by hand if you want them to survive. So you put a dive hut over the ice, sit on the edge and plop in, like you’re going into a swimming pool. There are a couple feet of ice you have to go through to get down. In the few seconds it takes to do that, I feel like I’m transporting through a black hole to another planet, because it’s such an otherworldly ecosystem.

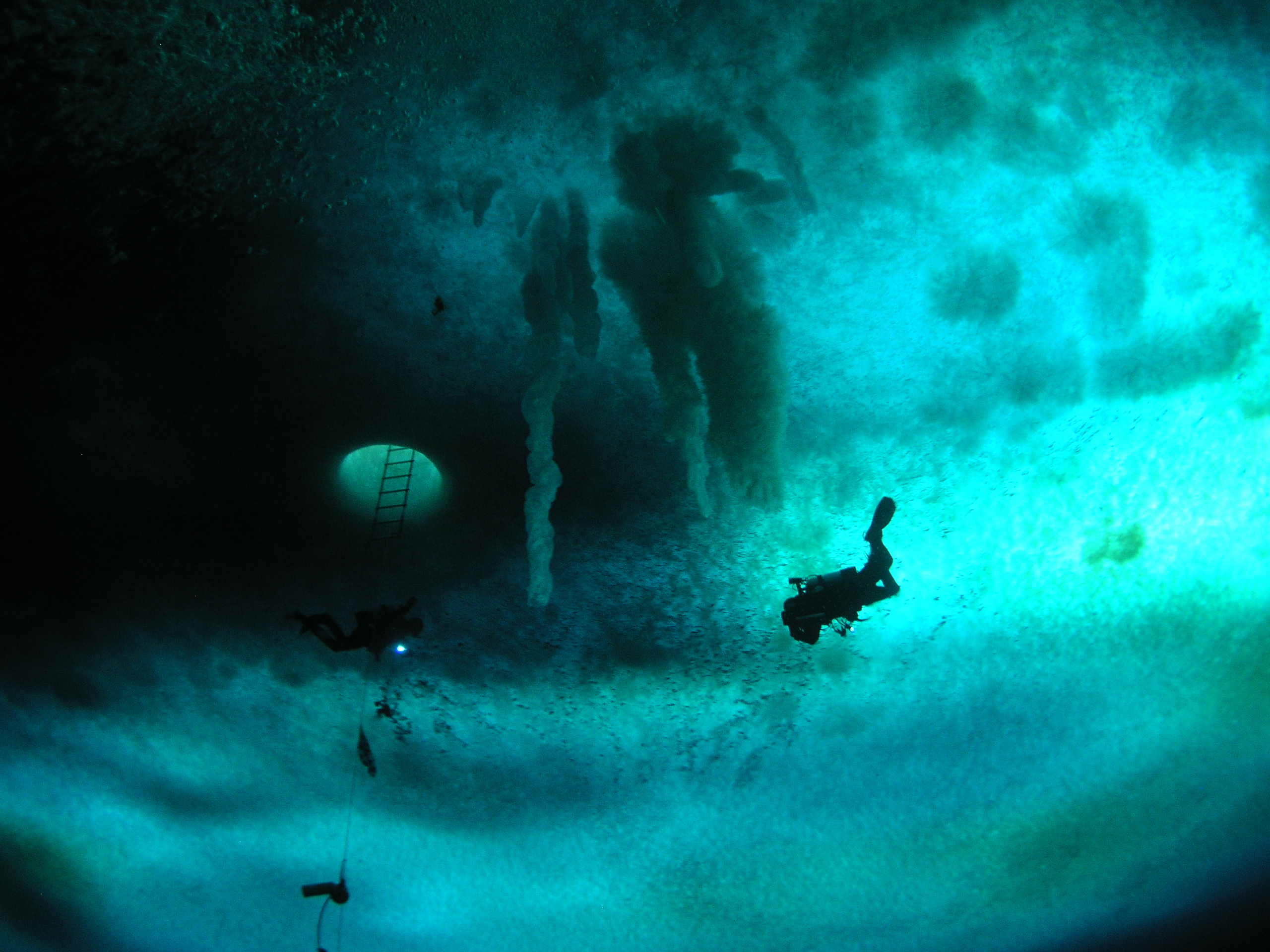

I’m really interested in ice habitat for the fish, and I’m obsessed with sea ice. On the top, the ice is flat from the wind and stuff, but when you go underneath, there’s all this structure that forms. It’s like an “ice reef” because of all the structures. I love that.

That’s also where emotion ties in, because I feel really sad that the ice is disappearing. Sea ice is such an important piece of the ecosystem, and I think we’re only just starting to understand that more in terms of smaller critters.

The water is crystal clear at the beginning of the season, so you can see for hundreds of feet. That’s not normal for diving, especially in California, where it’s like, “Great, I can see 20 feet today!” So it feels like swimming through this alternate planet.

Everyone’s like, “Is it cold?” Yeah, it’s cold! Dry suits leak and compress. Often toward the end of a dive I’m so cold, but I want to stay because it’s so beautiful that I just want to have time to explore. You come up, and your cheeks and lips are all puffy from the cold water. Your face is all red from the blood coming back. But it’s just stunning, is all that I feel. Being able to work there is what keeps me going, too. Thinking about how special it is that that’s what I get to study.

That sounds so amazing. I talked with Professor Tessa Hill for this series, too, about “the knowing.” Like when you study climate change, there’s a lot of joy in that because you get to be in these amazing environments and feel a sense of purpose. But “the knowing” changes how you see everything in your life. Are there ever times you wish you didn’t know?

My housemate and I joke, like, “Let’s just open a flower shop or own a bakery or something joyful.” But whether it’s just my generation or upbringing, the importance of climate change is something I’ve always known about. I see that with students who are now undergrads at UC Davis. Even my nephew and niece, who are 8 and 6, sometimes make drawings of wildfires and wildfire smoke. I’m like, wow. I think younger generations are just like, “This is what it is.”

I guess the difference for me is I feel there’s been a shift from environmentalism as “reduce, reuse, recycle” and individual actions as the answer to realizing the big drivers are the oil and gas industry, and the intentional propaganda and misinformation we’ve been exposed to for decades. I just get so angry at these companies and handfuls of individuals who have really changed our climate.

So what drives you to move forward with “the knowing?”

I ask other people that a lot, like, “How do you do this?” I feel like I do it not because I want to but because I have to, almost. I’m in this.

I’m thinking about what we talked about with the sexual violence work. This is so heavy and so hard, but you find community in it.

And the knowing part: Once you know, you can’t unknow. Now that I know, and I know I care about it, I have to keep working on it. That keeps me going. The thought of going back to the Antarctic, that also really energizes me.

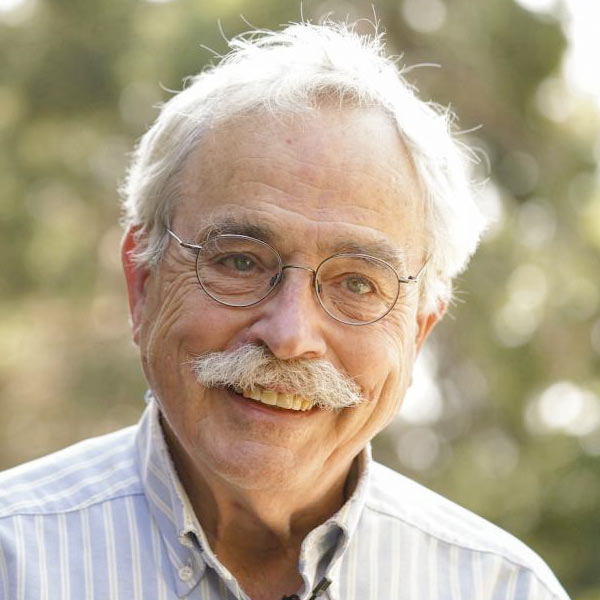

Restart the series with part 1, “Peter Moyle: Fish by Fish, Bird by Bird”

In part 1 of the “Confronting Climate Anxiety,” series, fisheries biologist Peter Moyle tells us why he’s still so optimistic despite a half century of chronicling the decline of native fishes in California.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin is an environmental science writer on the UC Davis News and Media Relations team. 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu. Twitter @UCDavis_Kerlin.