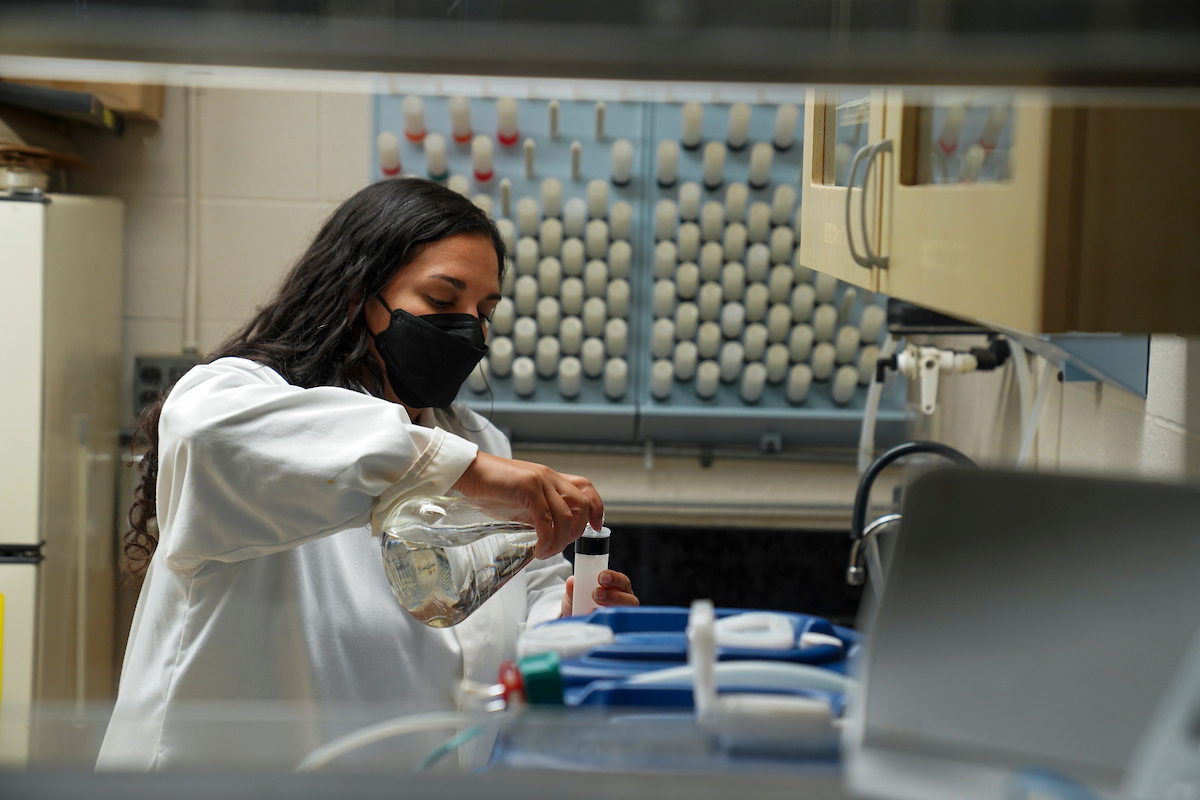

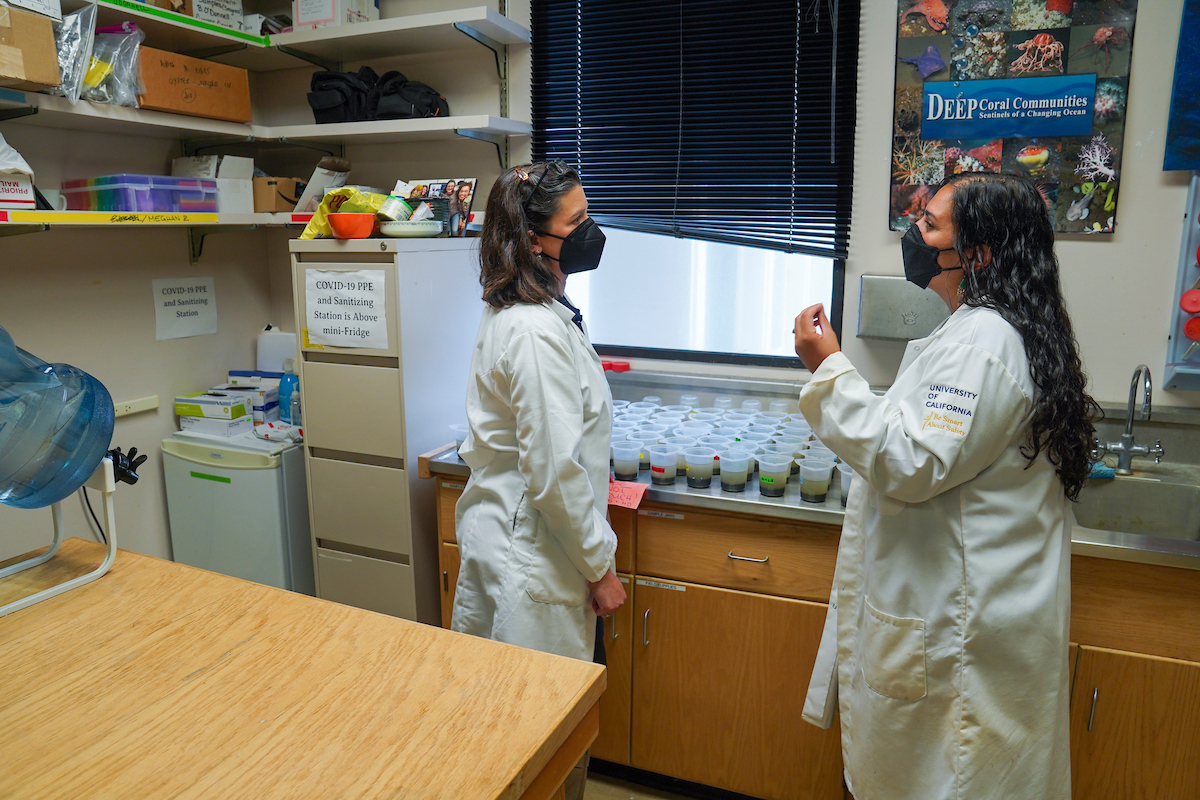

Both wetsuit and lab coat constitute office attire for scientist Alyssa Griffin. She’s on a search for blue carbon – the carbon the ocean stores within its sandy seabed, coral and blades of seagrass — and ways to better capture and store it to help reduce the impacts of climate change.

This article is part 6 of the series “Confronting Climate Anxiety”

View all eight parts of the series, and find out what scientists are doing to turn climate anxiety into climate action.

A former member of Tessa Hill’s lab at Bodega Marine Laboratory, she’s a newly appointed assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Davis. She has also received honors for her work toward justice, equity, diversity and inclusion in science.

What were some of your first experiences with the ocean?

My family used to visit the Jersey Shore — not that “Jersey Shore.” This was southern New Jersey, also Delaware, Maryland, Cape May. I just remember loving the beach and the ocean and spending time there with my family. I always associated it with good, warm feelings.

I entered undergrad as a music major. I never thought I was good at math or science. I loved nature but was intimidated by the “hard sciences.” Looking back, I think a lot of that had to do with not seeing representation of people who looked like me in my science courses or the media, which fueled my insecurities.

I was required to take a science course in college, and I chose geology because I heard it was easy. [Laughs.] I absolutely fell in love with Earth science. I was immediately humbled by the scale of our planet — the insignificance of our planet within space, and the insignificance of our lifetime in the space of geologic time. To me that was just poetic.

Yet despite our apparent insignificance, I learned we were still capable of impacting something as large as our climate over a short geologic time. That got me interested in the global carbon cycle and in carbon capture and storage strategies.

The storage capacity of the ocean for carbon dioxide is immense! The ocean takes up about 30% of the emissions we release annually. Without the ocean, the fight against climate change would already be over.

Currently my research is focused on trying to build capacity in coastal ecosystems to capture and store carbon. Systems that hold a lot of carbon in their sediment are known as blue carbon systems — seagrasses, kelp forests, tidal marshes and mangroves are the four canonical ones.

They can store carbon in their actual blades of grass, stalks of algae, mangrove trunks and leaves. They can also store carbon in the soil underneath them, similar to how carbon is stored on land. Soil in the coastal ocean just happens to be underwater. So I take those sediments and see how much carbon is inside them and why some places have more carbon than others.

Without the ocean, the fight against climate change would already be over.

How have your perceptions about climate change and the ocean shifted since you began studying it so closely?

Like a lot of folks, my understanding of environmental science, justice and care started from an individualist perspective of, “I need to recycle and ride my bike and take these individual actions that, while very important, are actually just a drop in the bucket of the things we really need to address.”

Now, it’s very clear that the vast majority of the emissions causing climate change are from a handful of companies. So when you shift that responsibility, it creates a clearer picture of the problem we should be working on the most. We need to be holding those companies accountable.

The other piece that’s shifted is knowing that even if we decided the whole world wouldn’t emit another molecule of carbon into the atmosphere, it still won’t be enough to prevent catastrophic change. We need to reach net negative emissions. So whether we want to or not, we have to think about ways to capture and remove carbon from the atmosphere.

I previously thought the Earth is so good at doing this itself because it’s regulated its own climate for so long. But the data show we now need to do something additional to offset the path we’re on. A lot of the work I do is about how we can take natural systems and processes that the Earth has perfected over millions of years and use those to take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. It’s no longer enough to just stop emitting carbon. We also need to capture it and remove it.

The other piece is more personal. It’s been about 13 years since I started doing this research. In that time, I became a mom. Even though I’ve always cared deeply about this topic, after becoming a parent, the sense of urgency really just washed over me. Now, it’s not like, “Oh, by 2100, I’ll be however old or dead.” It’s “Oh, 2100 — that’s in my daughter’s lifetime.” She will be living through what 2100 looks like.

Does your research make dealing with climate anxiety better or worse?

I can’t imagine doing anything else. When the climate crisis becomes real and tangible for all of us — which it will — I want to be able to look at my daughter and say, “I did my best.”

I’m not the kind of person who can see a problem and walk by. I didn’t get into geochemistry because I wanted to do climate change work. I got into it because I liked it, and it was fun. It so happens that it is also one of the best ways I can use my skills to help other people and this global issue.

That said, a lot of days are really hard. Everyone wants to unplug from work sometimes, but it’s hard to unplug because it’s all around you, all the time. So many societal issues are either related to or are going to be exacerbated by climate change.

Some people experience climate anxiety like stages of grief that come in waves. Does that resonate with you?

Yes, I’ve experienced those. There’s always been people with the perspective of “Humans are just a blip in geological time, we’ll all be dead and gone, and Earth will take care of itself.” To be fair, they’re not wrong.

But my philosophy has always been that we’re guests on this planet. Even if we’re only here for a short time, you would never to go to someone’s dinner party, trash their house, throw all the food against the wall, break some dishes, walk out the door and just say, “They’ll clean it up when I’m gone.” At least I hope you wouldn’t! Is that really what we want the legacy of our species to be?

So yeah, I have times when it feels overwhelming and like we’re just yelling into the void, but what’s the alternative? I don’t think apathy and defeat will get us where we need to go.

How do you take care of yourself when you feel the anxiety creeping in?

Ironically enough, I go out into nature. One of the biggest ways I reset myself is being in community with other people and nature to remind myself what I’m doing this work for. I think a lot of the guilt and anxiety comes from feeling so small. We are small, and that’s OK. That’s why the response to climate change really needs to be an all-hands-on-deck issue. We need each other’s skills, talents and perspectives to build a future capable of dealing with climate change in a just and equitable way.

You’ve mentioned privilege. How do you think it plays into climate anxiety?

As humans, we need certain basic resources to survive — food, shelter and water. If you don’t have those first three immediate things, it’s very difficult to care about other issues, which is part of the reason why climate grief and anxiety as concepts are very much a privilege.

Where it becomes complicated is climate change right now, as we speak, is threatening folks’ food, shelter and water. It’s happening here in our own state. For example, when there’s wildfire, you’re not thinking of climate change. You’re thinking, “There’s a wildfire, and I need to evacuate my house.” Another example is the drought, which should be alarming all of us. So this is not some far-off distant future; it’s real and now.

We’re not separate ‘stewards’ of the planet — we are the planet.

And it’s happening around the world. Many small island nations will be completely underwater with 2 degrees of warming. Imagine the entire U.S. underwater tomorrow. Those are the levels of threats we’re talking about to those communities. All of those nations put together are responsible for 0.003% of those emissions.

So it’s not just disproportionately affecting disadvantaged communities and people of color; it’s affecting people who had the least amount of responsibility for it in the first place.

For folks with the privilege of climate grief who aren’t being impacted by immediate threats, we have the responsibility to use that grief in a meaningful way, because we have the capacity to address climate change in a broader sense.

How can we talk about climate change so it helps people act, not just despair?

I think we have to acknowledge the gravity of the situation as step one. There’s a place and a time for climate grief. But if you let grief consume you, it doesn’t help you, or anyone, and it doesn’t honor what you’ve lost. I think using our grief as a fuel to fight for the things we have left is where you strike that balance.

What do you love about your job?

Um … everything? I love knowing that I get to wake up every day and do something that I really feel benefits people and the world.

As your daughter grows, she’ll look around and ask questions about her world. What do you think you’ll tell her about the changes she sees?

We can’t protect things that we don’t care about. For me, for my daughter’s future, I think it’s absolutely imperative to cultivate not just a care for nature, but to see ourselves as part of nature. We’re not separate “stewards” of the planet — we are the planet. This is the ecosystem hurling through space that we’re all in together. So cultivating a care for nature and for people — if founded on that perspective, I think she’ll make great choices. At least that’s my hope.

Continue the series with part 7, “Eric Post: Arctic Awe and Anxiety”

In part 7, UC Davis polar ecologist Eric Post changed his approach to teaching climate change after students began breaking down in class over the topic.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin is an environmental science writer on the UC Davis News and Media Relations team. 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu. Twitter @UCDavis_Kerlin.