Rugby’s return to the Olympic Games this summer calls to mind an ace athlete alumnus.

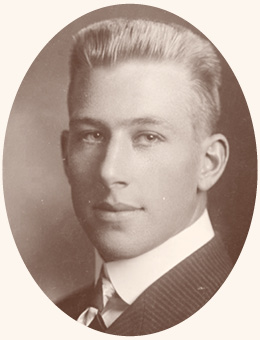

He was tall, agile and fast, a natural at basketball and football. Put all that together, and he was great at rugby—a gold-medal winner with the U.S. team in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics. Colby E. “Babe” Slater ’17 was the first Aggie alumnus to win Olympic gold, a member of the Cal Aggie Athletics Hall of Fame and the International Rugby Hall of Fame.

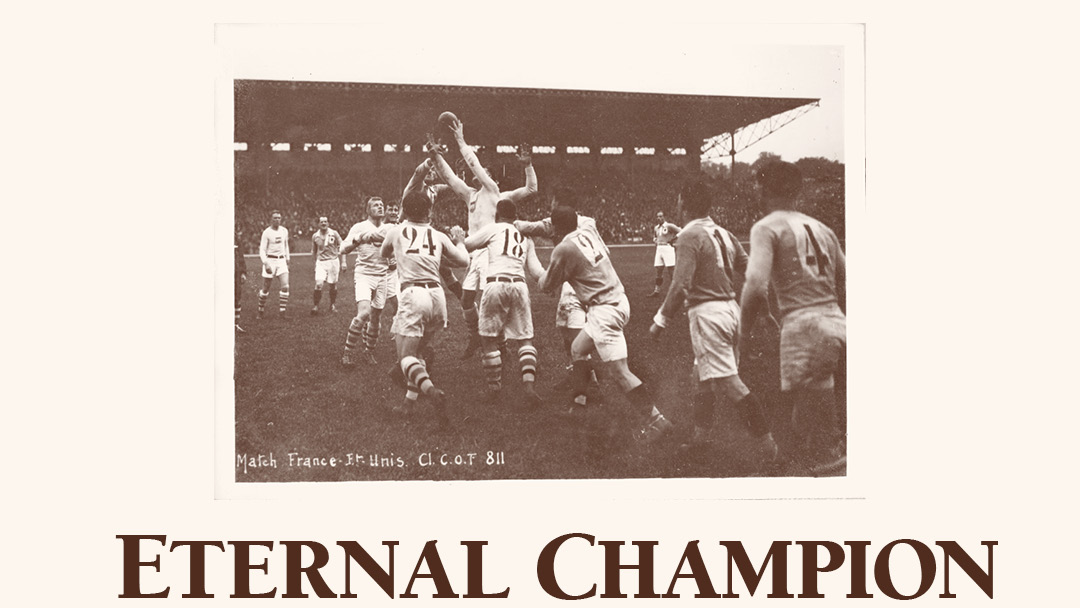

His legacy looms even larger this summer with rugby’s return to the Olympics after a 92-year absence, dating back to that 1924 gold-medal game when the U.S., with Slater as the captain, defeated the host country, France. That makes the U.S. the defending champion among the 12 teams that will play in the Games in August in Rio de Janeiro. The American women will play, too, in rugby’s debut as a women’s sport in the Olympics.

Another big change: The men’s and women’s divisions will play “sevens” (denoting how many players to a side), shorter in time and quicker in tempo than the traditional rugby that Slater played (15 to a side), but still with the tries and scrums and lineouts and backward passing that define the game.

“I imagine Babe Slater would have been a great sevens player because he was big, strong, and fast, and that’s ideal for sevens,” said Steve Gray, former coach of the UC Davis men’s rugby club and a former member of U.S. national squads, both 15 to a side and sevens.

Americans unfamiliar with rugby are in for a wild ride when they watch this summer. “The thing about a sevens game, it’s actually much easier to understand than a 15s game,” said Mike Purcell, former men’s club coach and also a former national player. A game lasts only 15 minutes, with two seven-minute halves and a one-minute break. And, with only seven on a side, on a full-size field (about 10 yards longer and 20 yards wider than a football field), “there’s a lot of space to do things. You’ll see a lot more long runs, breakaway runs, pretty intricate passing sequences.”

Slater’s path to Davis and Olympic gold is the stuff of Aggie legend, a story that is preserved in the University Library’s Colby E. “Babe” Slater Collection, a gift to Special Collections from his late daughter, Marilyn Slater McCapes ’55, and her husband, Dick McCapes ’56, D.V.M. ’58, who is retired from the faculty of the School of Veterinary Medicine.

Slater was a city boy, born in San Francisco in 1896 and reared in Berkeley, the youngest of four children. He and his brother Norman played on the Berkeley High School rugby team that won the state championship in 1912, and Babe participated in athletic events at his hometown university — but he never studied there, despite the fact Cal claims him as one of its own, listed with nine other alums who competed in the 1920 and ’24 Olympics.

Yes, the University Farm was officially a branch of UC Berkeley’s College of Agriculture, but make no mistake: Slater “became the quintessential Aggie,” McCapes said. He doesn’t know why Slater came to the University Farm, but figures he might have enrolled as a way to finish high school, which he had to forgo after his father died. Slater’s older sister, Marguerite, while studying at Cal, had been one of the first three women to take a course on the Davis farm — and she might have gone home with good things to say about the campus.

And so Babe Slater arrived in Davis in 1914 for a three-year program of agricultural training that included a high school diploma. He played rugby, football, basketball and baseball, and participated in other activities as well, serving as class president, Picnic Day Parade chairman and Picnic Day general chairman.

He graduated, served in the Army Medical Corps in France during World War I, then came “home” to Yolo County, farming around Woodland and eventually buying his own place in Clarksburg. “He liked the lifestyle,” McCapes said. “He could make his own decisions, he could do what he wanted, and it was a type of life that was very attractive to him.”

Slater began playing rugby in the early part of the 20th century, a time when the country turned to the sport as a safer game than football. But American rugby teams generally did not fare well in international play, and football made a comeback (with new rules). Californians stuck with rugby longer than the rest of the country, so the U.S. Olympic Committee knew exactly where to look when it formed a team for the 1920 Games in Antwerp, Belgium. And soon Slater was sailing to Europe with the rest of the all-California team.

Only two teams competed in Antwerp: the U.S. and France, and the latter had the edge, considering most of the U.S. players were fairly new to the sport. Before a crowd of 20,000, the Americans pulled off an upset, 8-0, in the rain. “At a council of war we decided that because the ground was wet and slippery and the ball likewise, we would make it a forward game,” reported Rudy Scholz of the University of Santa Clara, one of the players. “The French tried a backfield game, and they lost although they were fast. The slippery ball and field proved their undoing. Our forwards outweighed the French easily, and Babe Slater was a wonder in the lineouts”—when a player throws the ball in from the sideline, hopefully to be caught by a tall, leaping teammate.

Slater stood about 6-foot-4 and “was very effective in jumping high for lineout throws,” McCapes said. (Today, by the way, players will lift their teammates by the legs, during lineouts.)

Four years later, Slater was the first picked for the national team that would go to the Paris Games (his brother Norman also made the team). When all the boys boarded the train in Oakland, “the first thing the team did was elect Babe Slater as captain of the team,” McCapes said, citing the U.S. Olympic Committee’s report of the 1924 Games.

The U.S. and France easily defeated the Games’ only other competitor, Romania, setting up another U.S.-France match for the gold. The Americans prevailed, 17-3, and the game ended with the French fans in an uproar. And while some believe the fan reaction was the reason for rugby’s disappearance from the Olympics, other histories ascribe it more to the fact that Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the French educator who brought back the Games in 1896, had stepped down as the Olympics president. His successor did not share de Coubertin’s enthusiasm for rugby, and, in fact, steered the Olympics away from team sports.

In describing why he admired rugby, de Coubertin cited the sport’s moral values as well as the physical and mental skills required to play it — almost as if he were talking about Slater himself. “He was an effective leader,” McCapes said. “He was quiet-spoken … and had a great inner strength to him.”

Today, his strength and spirit live on in a new generation of Aggie rugby players. In 15s play, the men’s sport club won its conference this season and has a good chance to repeat as the national D1AA champion. The women’s sport club, meanwhile, completed conference play as the top-ranked D1 team in the nation.

Babe Slater would be proud.

At the library

The University Library is sharing its Colby E. “Babe” Slater Collection in two exhibits — one in Shields Library and one that’s online, scheduled to go live in early 2017. The library exhibit, which will be on display through Dec. 31, features photographs, correspondence and personal memorabilia from Slater’s participation in the 1920 and ’24 Olympic Games.

The complete collection extends to Slater’s time as a UC Davis student, his participation in the first World War, and his life as a farmer and active member of the community in Yolo County. The online exhibition is a product of the library’s digital expansion, which is helping preserve and provide greater access to historical collections and UC Davis research.