Senegalese author and feminist Mariama Bâ is known for her French-language novels “So Long a Letter” and “Scarlet Song.” She became, before her death in 1981, one of the 20th century’s most written-about and widely taught authors.

Now, because of research by Tobias Warner, an associate professor of French at University of California, Davis, a forgotten poem she wrote before her novels is now receiving attention. How did this piece of work become lost to history?

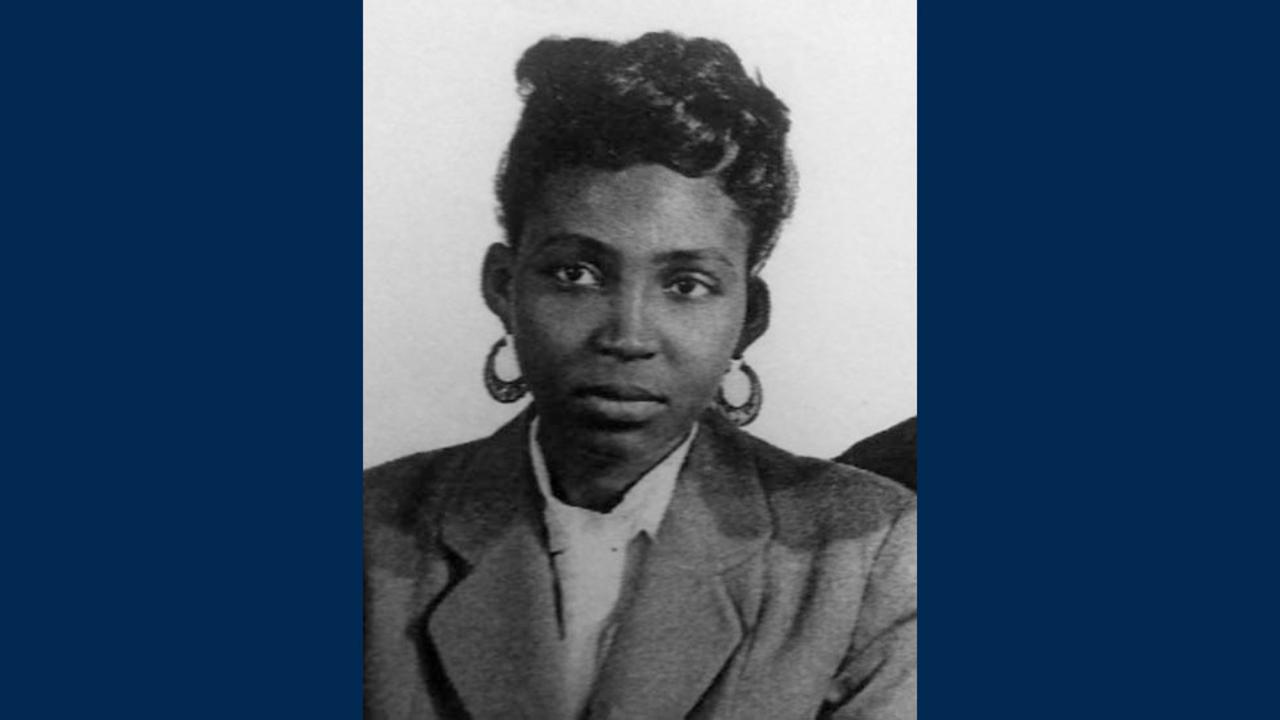

“There are several possible reasons for this,” Warner, an African Literature scholars, said in a paper published this month in the journal Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. “The simplest reason is that Bâ published the poem under her married name. Helpfully for the purposes of attribution, L'Ouest Africain (her husband’s newspaper) ran a photo of the author beside the text, and ‘Mariama Diop’ is by all appearances the same person as the author of So Long a Letter.”

But Warner said it also has to do with the kinds of questions researchers ask. “Bâ was known as a novelist,” he said. “The folks who studied and taught her work, myself included, tended to turn to her novels. No one was looking for what she might have written in newspapers and magazines.”

When a poem goes missing like this, access is another factor.

“We live in an age of digitization, but that digitization is very uneven,” he said. “There’s really a question of global cultural equity when a text by one of the most important and widely taught African novelists of the 20th century goes under the radar like this. You can imagine that for equivalent publications from the 1970s that were published in the United States or France, they’re much more likely to be digitized or easily accessible."

The poem, which translated means “Memories of Lagos” sheds important new light on Bâ's poetic work and above all on an underappreciated Pan-African dimension to her thought, Warner said. Bâ is not listed among the sizable (all male) official Senegalese delegation at the festival she wrote about in the poem.

“It puts Bâ in the room with just an incredible range of people who are showing up to this event, and it’s not something that many people knew she was at,” Warner said.

The poem records Bâ's experiences at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, held in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1977. This important Pan-African gathering drew more than 16,000 performers and attendees from across the continent and its diaspora for a celebration of African arts and culture. Bâ was in Lagos to represent L'Ouest Africain (The West African), a newspaper (and later magazine) published in Dakar under the editorship of her husband, Obèye Diop.

“What Bâ took from Lagos was hope, a hope that remaking Africa was possible,” Warner wrote. He said in her novels such optimism is tempered by the conviction that any decolonial remaking must also reckon with gender inequality and oppression.

Strikingly, in this poem's last, hopeful image, Lagos is proclaimed to be the seed of a new future, Warner said in his paper.

"This vision of germination would be transposed into the closing lines of “So Long a Letter,” where Bâ's protagonist Ramatoulaye compares her own difficult past to “de l'humus sale et nauséabond [d'où] jaillit la plante verte” (“the dirty and nauseating compost out of which the green plant sprouts”; Une si longue 165; my trans.).”

"Bâ's novels went on to worldwide acclaim. This little-known poem suggests that the spark that lit them was transnational and pan-African.”

Warner is now working with colleagues to prepare a special section of PMLA that will focus on Bâ’s poem.

Read how this research came about, and excerpts of Bâ's poetry in this story on the College of Letters and Science website.

Media Resources

Media contacts:

- Greg Watry, College of the Letters and Science, gdwatry@ucdavis.edu

- Karen Nikos-Rose, News and Media Relations, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu