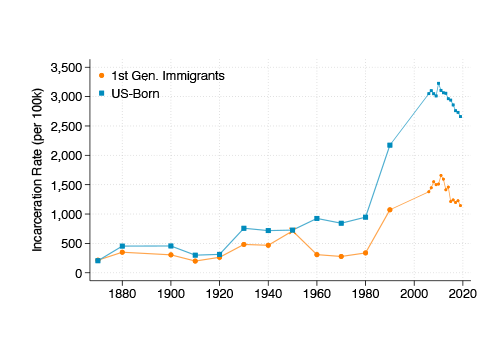

For the past 150 years, immigrants in the United States have had lower incarceration rates than those born here, and new research shows that since the 1960s that gap has significantly grown.

This new analysis was a data-driven effort to compare the rates at which immigrants and people born in the U.S. commit crime. This paper is also the first to compare incarceration rates over such a long period of time. It is currently published as a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

“We are really able to establish this fact, which I think is quite striking, that in the last 150 years there's never been a time in American history where immigrants have higher incarceration rates than the U.S.-born,” said Santiago Pérez, an associate professor of economics in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science and a co-author on the paper.

Comparing incarceration rates between immigrants and the U.S.-born

“We are really able to establish this fact, which I think is quite striking, that in the last 150 years there's never been a time in American history where immigrants have higher incarceration rates than the U.S.-born.” — Santiago Perez, associate professor, economics

The economic analysis is based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau starting in 1870. Once every ten years, the U.S. Census counts every person in the country. This includes people who are in prisons. It also includes people without regard to their immigration status.

The team included Pérez, Ran Abramitzky and Juan David Torres from Stanford, Leah Platt Boustan from Princeton and Elisa Jácome at Northwestern University. Their analysis found that for most of the period since 1870, incarceration rates between immigrants and the U.S.-born were about the same.

However, in the early 1960s, incarceration rates among immigrants began to decline relative to the native-born. Today, the immigrant incarceration rate is about 60% lower than for all people born in the U.S. Also, immigrants from all major country-of-origin groups have had a similar decline in incarceration rates compared to the U.S.-born.

This graph shows incarceration rates among U.S. immigrants and the native-born from 1870-2020 per U.S. Census Bureau Data. Figure courtesy Santiago Pérez.

The team explored a number of potential explanations for this shift that began about 60 years ago. One might have been that deportation was removing more people from the country before they could be counted by the U.S. Census. However, mass deportations in the U.S. began in the early 2000s, well after the incarceration trends for immigrants and the native-born began following different paths.

Another explanation might have been that immigrants after 1960 were more highly educated as a group than in prior years. Historically, the higher a person’s level of education, the less likely they are to be incarcerated. This turned out to be another dead end. Education levels among immigrants relative to the U.S.-born were at or below what they had been before.

U.S.-born struggling more than ever

Pérez said he began to think that the issue had less to do with changes in immigrants’ incarceration rates than it did with rapidly increasing incarceration rates among the native-born.

“We ended up noticing that a lot of the story seems to be about how the U.S.-born, particularly the least educated U.S.-born, are struggling along a number of dimensions,” said Pérez. “What really explains this widening of the gap is not so much that the immigrants are getting better but that the U.S.-born are deteriorating at a fast rate.”

For example, in the past, immigrants without a high school degree were employed at similar rates than their US-born counterparts but are now 30 percentage points more likely to be employed today. Immigrants without a high school degree are roughly 20 percentage points more likely than U.S.-born men to report “excellent” or “good” health.

“When you look at indicators of the likelihood someone will have a job or get married and have kids, or even at self-reported levels of health, immigrants actually seem to be doing quite well compared to the native-born,” said Pérez.

Overestimating danger to society

It could be that incarceration data itself misrepresents the actual question Pérez and his team intended to ask: do immigrants commit crime at higher rates than people born in the U.S.? This is where U.S. Census Bureau data has its limitations.

When a person is reported as incarcerated to the U.S. Census Bureau, that data does not include any reference to their crime. For an immigrant who comes to the country outside of legal channels, they can be charged with a crime and incarcerated. So even if the only law they broke was entering the U.S., they are still reported as an incarcerated individual.

“Ideally we would like to know the type of offense for which people are incarcerated,” said Pérez. “Not having formal authorization to be in the country is one definition of crime, but it's not clear whether people who commit that crime are necessarily a threat to personal safety.”

This also means that if a large share of crimes among immigrants is related only to having entered the U.S. without authorization, removing them from the data would drive down overall incarceration rates for immigrants even lower.

Pérez said that these results challenge a popular nostalgia about past waves of immigrants compared to immigrants coming to the U.S. today.

“People often see past migration waves in a more positive light,” said Pérez. “They think about Europeans who came in the late 19th century and early 20th century and they tend to contrast this with new migrants, but what we find in the paper is actually the opposite.”