When the Pacific Ocean sloshed warm water back toward Peru in the 1500s, the country’s fisheries collapsed around Christmas time. A name was born: “El Niño: The Christmas Child.”

“It’s the little child of Christ who is causing problems,” said UC Davis Atmospheric Science Professor Ian Faloona.

El Niño is expected to be causing problems, again, from now and through this winter. UC Davis experts weigh in on the knowns and unknowns of what California and the rest of the world may expect.

What about California?

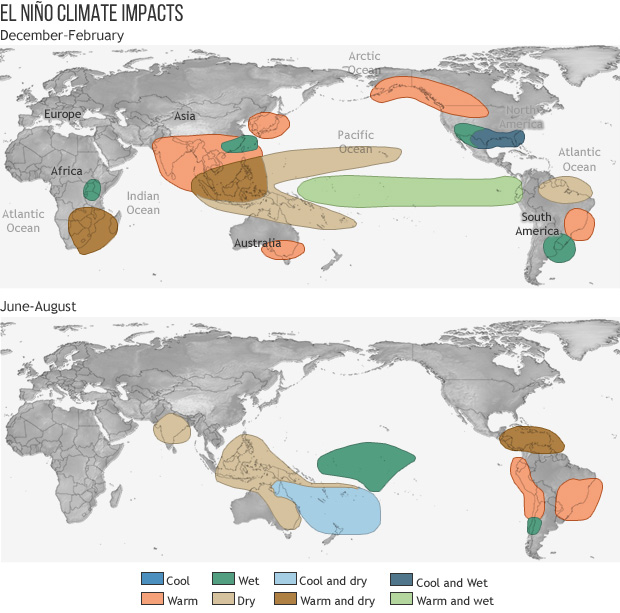

Even though global temperatures increase with El Niño, impacts are not the same everywhere. The West Pacific, like Southern Asia and Australia, may experience drought, while the East Pacific, like Peru and Southern California, may experience a very wet winter.

This Eastern Pacific coast normally experiences upwelling of cold, nutrient-dense water from powerful winds pushing the water away from the coast into the Pacific. But when these trade winds weaken, warm water is pushed back toward the coast and results in powerful storms. This is El Niño, while La Niña occurs when these winds strengthen.

The warm water location change is linked to where moist, hot air rises in worldwide convection currents, which can cause major shifts in storm structure and dynamics across the globe.

But although Southern California is forecasted for rain, the Pacific Northwest is expected to experience drying, leaving the Central Valley right in the middle.

“The effects sort of miss us, in a sense,” Faloona said. “We’re kind of in this transition zone.”

However, the Central Valley should receive more water from increased snowfall in Southern California mountain ranges. Good news for California skiers and snowboarders.

But why?

The Chimú people of Peru believed that El Niño was caused by angry sea gods. Today, El Niño is still mystifying.

“Every 2-7 years, the winds seem to just weaken in the summertime,” said Faloona. “I think it’s very mysterious how it evolves.”

What triggers El Niño is a hot topic of research, and is something that Maike Sonnewald, UC Davis assistant professor of Computer Science, is hoping to dive deeper into over the next few years.

“El Niño is such an interesting phenomenon because it is effectively the ocean talking to the atmosphere and having this global conversation,” Sonnewald explained. “You can’t just look at the atmosphere; you can't just look at the ocean. You need to look at both.”

With trade winds, atmospheric convection currents, global storm structure, oceanic energy, and planetary movement all interacting with each other, it is hard to pin down cause and effect.

“Everything is coupled,” said Faloona. “It’s a little bit of a chicken and egg.”

A mysterious future

El Niño increases global temperatures overall, which can aggravate the effects of climate change and result in record high temperatures. With climate change, El Niño’s effects may also be more intense.

This dynamic is a tricky one to study. Although historical records of El Niño go back to 2,200 B.C, there are only around 12 fully comprehensive observations of El Niño in the past 40 years.

“It’s hard to say anything about a sample of 12,” Faloona said. “It’s easy to find something universal and be fooled by the low number of observations.”

This lack of data is why scientists rely so much on models. Sonnewald and her student, Zouberou Sayibou, worked with climate models to understand how El Niño will change under different climate and socio-economic pathways.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have data from the future. So we have to use models,” said Sonnewald.

Atmospheric Rivers and El Niño Experts

A list of scientific experts for reporters.

Sonnewald and Sayibou’s model analysis suggests that El Niños may increase in severity under climate change. Temperature anomalies like marine heat waves may also increase with the combination of El Niño heating and climate change. Still, with the complexity of El Niño’s patterns and the unknowns behind the phenomenon, much is still left to discover.

“It’s very uncharted territory,” Sonnewald said. “But I think we as a scientific community are ready for it. I’m excited.”

Present predictions

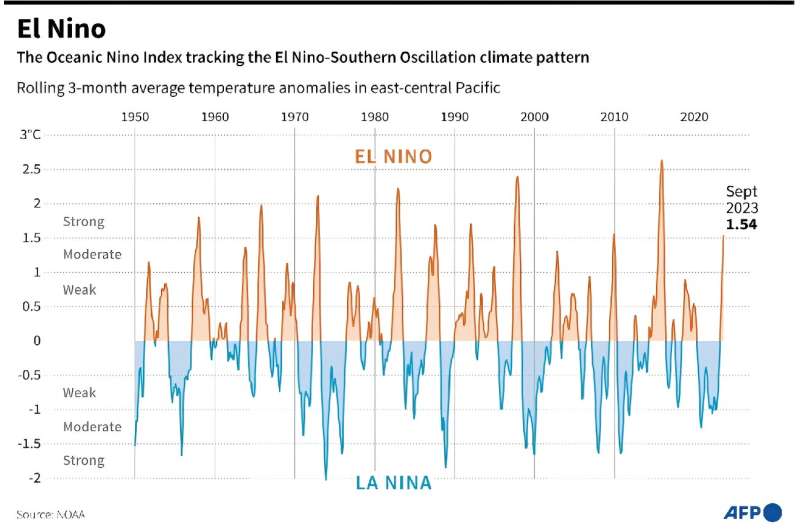

Predicting when El Niño will occur is also a mystery. However, once the events begin to form, scientists can predict intensity by taking the average temperature in a specific band of increasingly warm water around the equator. This temperature becomes the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI).

This index not only predicts how intense the event will be, but also how many people will be affected by El Niño. As of now, 110 million more people may be food insecure this winter because of reduced crop yields due to El Niño.

“We need to be able to tell local communities what they need to prepare for,” said Sonnewald.

But even if scientists know possible global impacts, local weather predictions under El Niño are difficult. A small anomaly “wobble” can be a big deal for places like California, said Sonnewald. For example, La Niña tends to average toward a drier Southern California, yet that region experienced flooding during last year’s La Niña.

“It is a chaotic system,” said Faloona. “Tiny, tiny changes can create a very different future for weather.”

Malia Reiss is a science news intern with UC Davis Strategic Communications. She studies environmental science and management at UC Davis.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu