Wildlife conservation sometimes involves eating fewer animal products. But to save California’s kelp forest, a new dish is being added to the menu: purple sea urchin.

A variety of factors, such as a decline of natural predators and warming waters, have led to an overpopulation of purple urchin, with millions of them now carpeting the seafloor. They can eat sponge and even rock, but kelp populations have been particularly decimated.

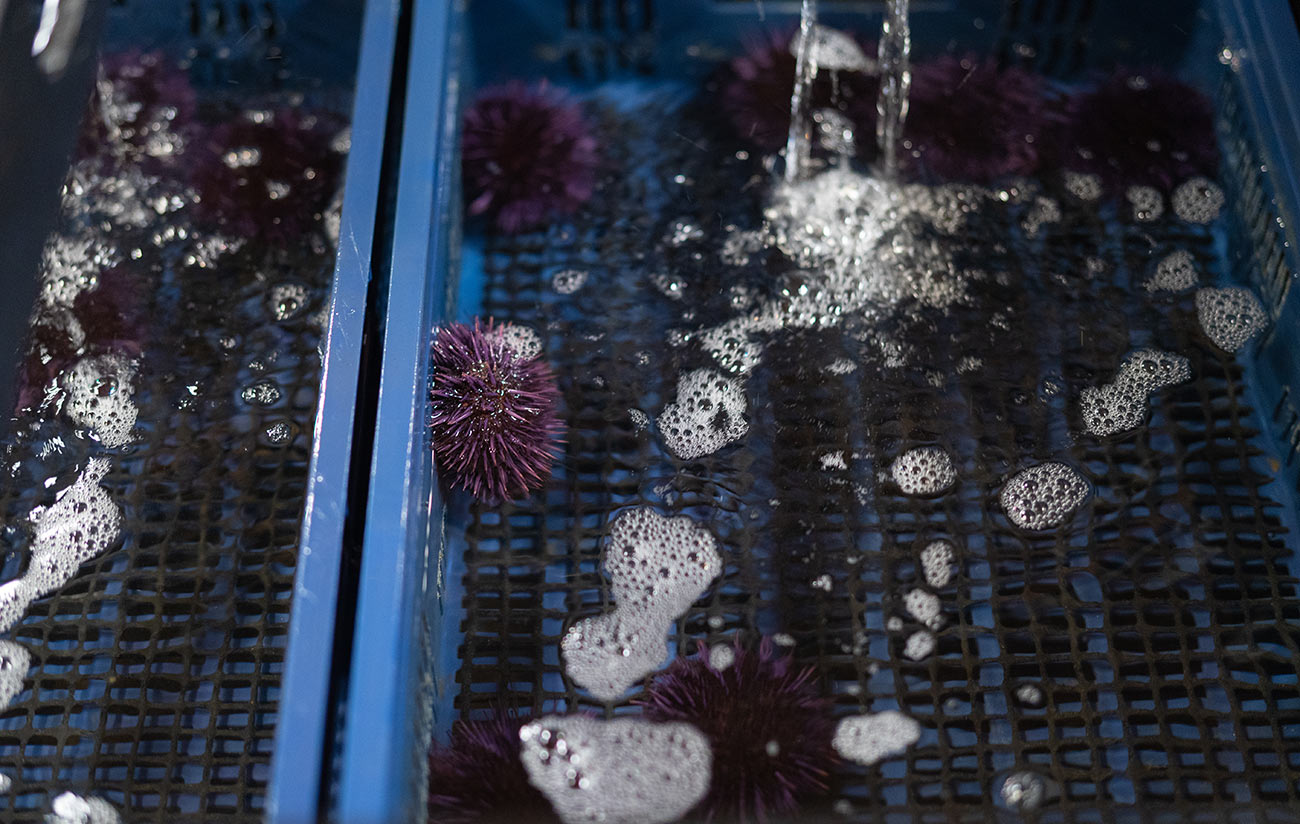

Urchin ranching trials are underway at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory. (Video: Alysha Beck/UC Davis.)

More than 90 percent of bull kelp were lost along northern California’s coastline within just a few years after purple sea urchin populations exploded between 2014 and 2015, according to a recent UC Davis study. The crash also triggered the close of the red abalone fishery.<

“Around 250 miles of coastline between California and Southern Oregon no longer has kelp forests,” said Karl Menard, aquatic resource manager at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory.

While the kelp may be crashing, it is not gone. Researchers estimate the kelp populations could regrow in six months with the right temperature conditions and without the masses of sea urchins. But how?

Urchin ranching

Enter urchin ranching.

Wild purple urchins are competing with each other for food, leaving many of them starving and practically empty inside, with none of the rich roe valued by consumers around the world.

Bodega Marine Lab and Norwegian-based shellfish company Urchinomics have partnered to test whether taking purple urchins from their seafloor barrens and fattening them up for market could be a viable strategy to reduce urchin populations, mitigate future damage, and potentially regrow California’s lush kelp forests.

“Solutions here would be solutions around the globe,” said Laura Rogers-Bennett, an environmental scientist with UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center and California Department of Fish and Wildlife operating out of the Bodega Marine Lab. Her recent study helped sound the alarm about crashing bull kelp forests. “Climate change is now, not the future.”

At the Bodega Marine Lab, wild purple urchins are placed in large, 12-by-12 tanks which can hold up to 800 urchins. They are fed an algae-based pellet diet to plump them up. Rich, orange roe develops after eight to 10 weeks, a far cry from the blank, empty, starving urchins found on the seafloor now.

Premium quality sea urchins can fetch between $8-10 dollars each, as compared to the current price of $1-2. This could help incentivize commercial fishers to pull in what Menard predicts to be thousands — and potentially millions — of sea urchins.

Voracious eaters

Though covered by sharp purple spikes, the urchin meat, or roe, is a soft, vibrant orange. Rogers-Bennett describes it as having a “creamy, buttery taste,” reminiscent of shrimp or oyster. These urchins seem equally likely to appear at sushi bars and supermarkets.

Denise MacDonald, director of global marketing for Urchinomics, notes a surprise demand for urchin roe with pasta dishes. But a steady supply of purple urchin can be hard to find.

“Nobody can supply consistent product in the urchin market,” MacDonald said.

Meanwhile, seemingly unstoppable kelp, which can grow up to 70 feet high, is being mowed off at the base by purple urchins with an appetite equivalent to “chewing through the trunk of a redwood tree,” said Rogers-Bennett.

They are eating themselves out of house and home. Once the kelp and other food is gone, some starving urchins even eat each other.

If urchin ranching works, it could be a win-win for both kelp and the seafood industry, helping to turn the tables on these voracious eaters.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-752-7704, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Laura Rogers-Bennett, UC Davis/CDFW, (707) 875-2035, rogersbennett@ucdavis.edu