In the past five years, collisions between wildlife and vehicles cost California at least $1 billion and potentially up to $2 billion, according to estimates in an annual report by the Road Ecology Center at the University of California, Davis.

The report presents an overview of collisions with large and small animals — from bighorn sheep, deer and bears to squirrels, birds and lizards. The Road Ecology Center mapped about 15,000 miles of state highways to identify stretches of highway where wildlife-vehicle collisions, or WVCs, are most likely to occur.

It names Interstate 280 as the “Deadliest Highway in California” for WVCs. This interstate on the San Francisco Peninsula runs between San Bruno and Cupertino. Five of the top-20 costliest segments are on I-280, costing the state around $178,439 per mile per year.

“These findings illustrate the tip of the iceberg of ecological and economic impacts that wildlife-vehicle collisions cause for California,” said lead author Fraser Shilling, director of the Road Ecology Center. “We need the Legislature to step in and help the good folks in transportation to fence the conflict hot spots and build many more wildlife crossings.”

Hot spots

The report is based on more than 44,000 California Highway Patrol traffic incidents involving large wildlife and more than 65,000 observations reported to the web app California Roadkill Observation System, or CROS, between 2009 and 2020. Anyone in California can collect roadkill data using the app.

In addition to I-280, key hot spots include:

- San Francisco Bay Area: U.S. 101 through southern Marin County; I-680, I-80, state Route 24 and SR 13 through the East Bay; and SR 17 near Lexington Reservoir

- Sacramento-Placerville Area: I-80, U.S. 50 and SR 49 in the Sierra Nevada foothills

- Central Sierra Nevada: SR 4, SR 41, SR 88, SR 108, and U.S. 395

- Northernmost region: I-5 between Lake Shasta and the Oregon border, SR 44 in Lassen County, U.S. 101 along the North Coast, and SR 20 near Clear Lake

- Southern California: I-405 and SR 2 in Los Angeles County; I-15, SR 67, I-8 in San Diego County; U.S. 101 and SR 154 in Santa Barbara County.

Mountain lions, bears and newts

The report highlights mountain lions, black bears and Pacific newts as cases where the problem is especially severe in certain places.

Mountain lions and black bears are vulnerable to traffic collisions because they often cross highways amid shrinking habitat. Between 2016 and 2020, more than 300 mountain lions and 557 black bears were reported killed on roads. Those numbers are considered conservative, because motorists are not required to report when bears or cougars are struck by vehicles.

“Populations of wildlife in the Bay Area have become isolated due to construction of interstates that bisect their home ranges,” said Katherine Boxer, chief executive officer of the Alameda County Resource Conservation District. “We are conducting research in the Altamont Pass and East Bay hills to identify locations to conserve lands and build wildlife crossings, which are critical to maintaining wildlife populations.”

One of the largest rates of roadkill reported for any wildlife species in the world occurs each year in California’s Santa Clara County, the report said. Pacific newts cross Alma Bridge Road while migrating from a forest to Lexington Reservoir, then return after reproducing. Along the way, 4,000-5,000 newts are killed each winter and spring by vehicles.

“It’s time we address how our roads are harming the state’s iconic wildlife, from mountain lions to Pacific newts,” said Tiffany Yap, senior scientist and wildlife connectivity advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The advantages to building more wildlife crossings couldn’t be more obvious. They help make roads safer for drivers and passengers while giving animals a way to roam and thrive.”

Road forward

In arriving at its $1 billion estimate, the Road Ecology Center drew from reports by CHP, volunteer observations of large roadkill, and U.S. Department of Transportation equivalent values for crashes. When including accidents reported to insurance but not to police, estimates rose to $2 billion for 2016-2020.

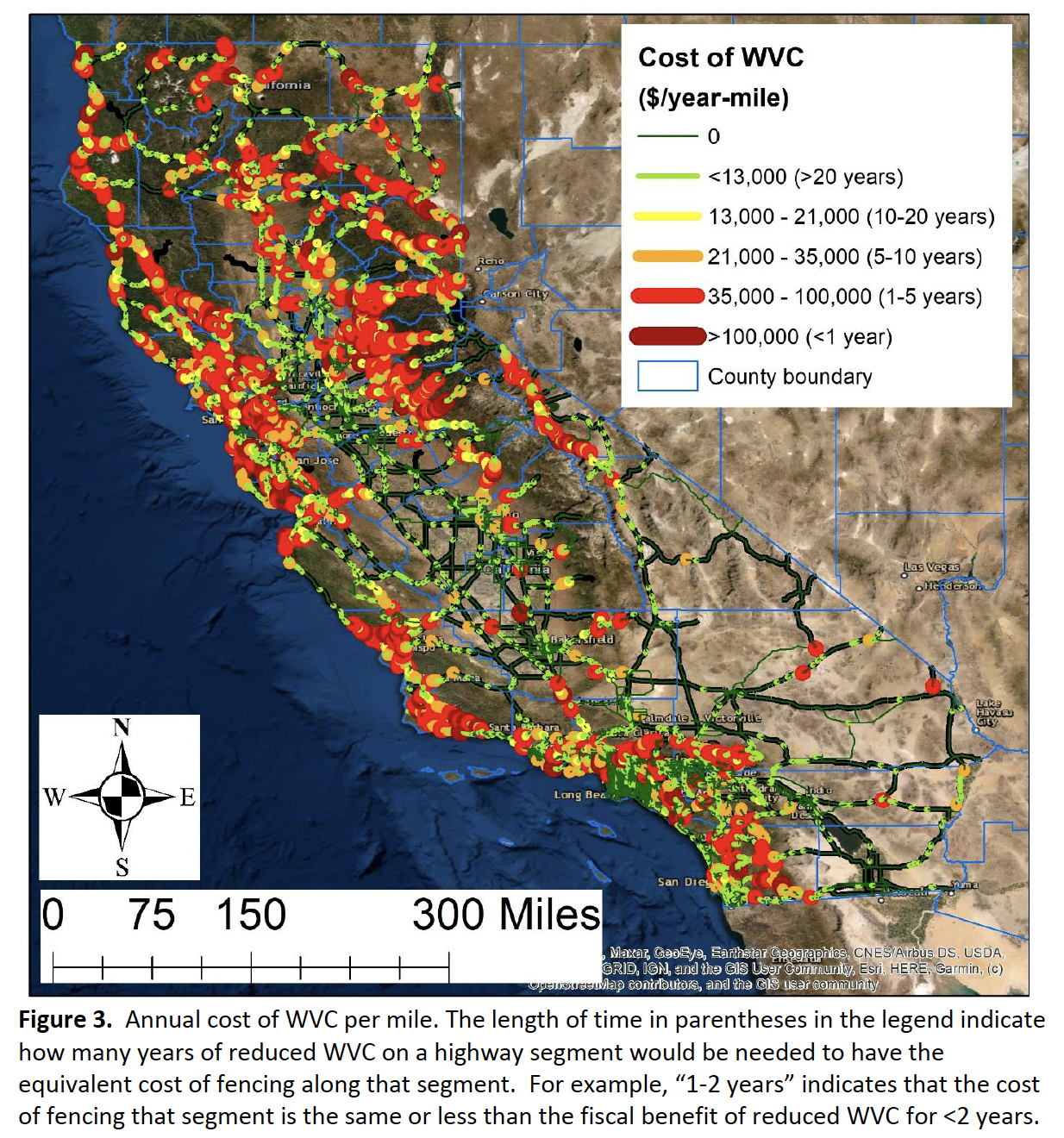

The report notes that the passing of Senate Bill 1 provided transportation agencies with an increase of more than $5 billion per year to protect driver safety and the environment. The authors encourage legislation that requires better and expanded infrastructure to allow for wildlife passage. The report identifies critical highway segments where the value of reducing conflicts between vehicles and animals would exceed the cost of building fencing. It estimates that treating 1,275 miles of such segments would cost around $175 million.

“In other words, this cost-effective method to reduce WVC impacts to wildlife and the driving public statewide would cost about the same as adding 1 mile of new lane to the I-405 in Los Angeles,” Shilling said.

The authors suggest such improvements be paid through transportation funds rather than more limited funding streams and urge these actions occur within a time frame that can prevent local extinctions and help restore impacted wildlife populations.

The report also provides several detailed examples, written by student interns, of projects in specific areas that could help reduce WVCs.

The report acknowledges support from the National Center for Sustainable Transportation, the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies and Pew Charitable Trust for supporting data collection and analysis tools used in the report.

Additional co-authors include David Waetjen, Graham Porter, Claire Short, and Morgan Karcs of UC Davis.

Media Resources

Media Contacts:

- Fraser Shilling, UC Davis Road Ecology Center, 530-219-3282, fmshilling@ucdavis.edu

- Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu