As wildfires become more intense and frequent, it’s important to learn all we can about these fires, how they work and how we can manage them.

Researchers at UC Davis have answers to your most frequently asked questions about wildfires.

1. What is the definition of a wildfire?

A wildfire is an uncontrolled, unplanned fire in a natural environment, like forests and grassland. According to UC Davis researchers, wildfires are crossing the wildland-urban interface more frequently.

The wildland-urban interface is where the wilderness meets with a well-populated area. A wildfire that crosses this divide becomes more dangerous because there is a higher chance of burning people’s homes and releasing toxic materials that can cause significant harm to humans and animals. It can also directly lead to more deaths.

2. Are wildfires caused by climate change?

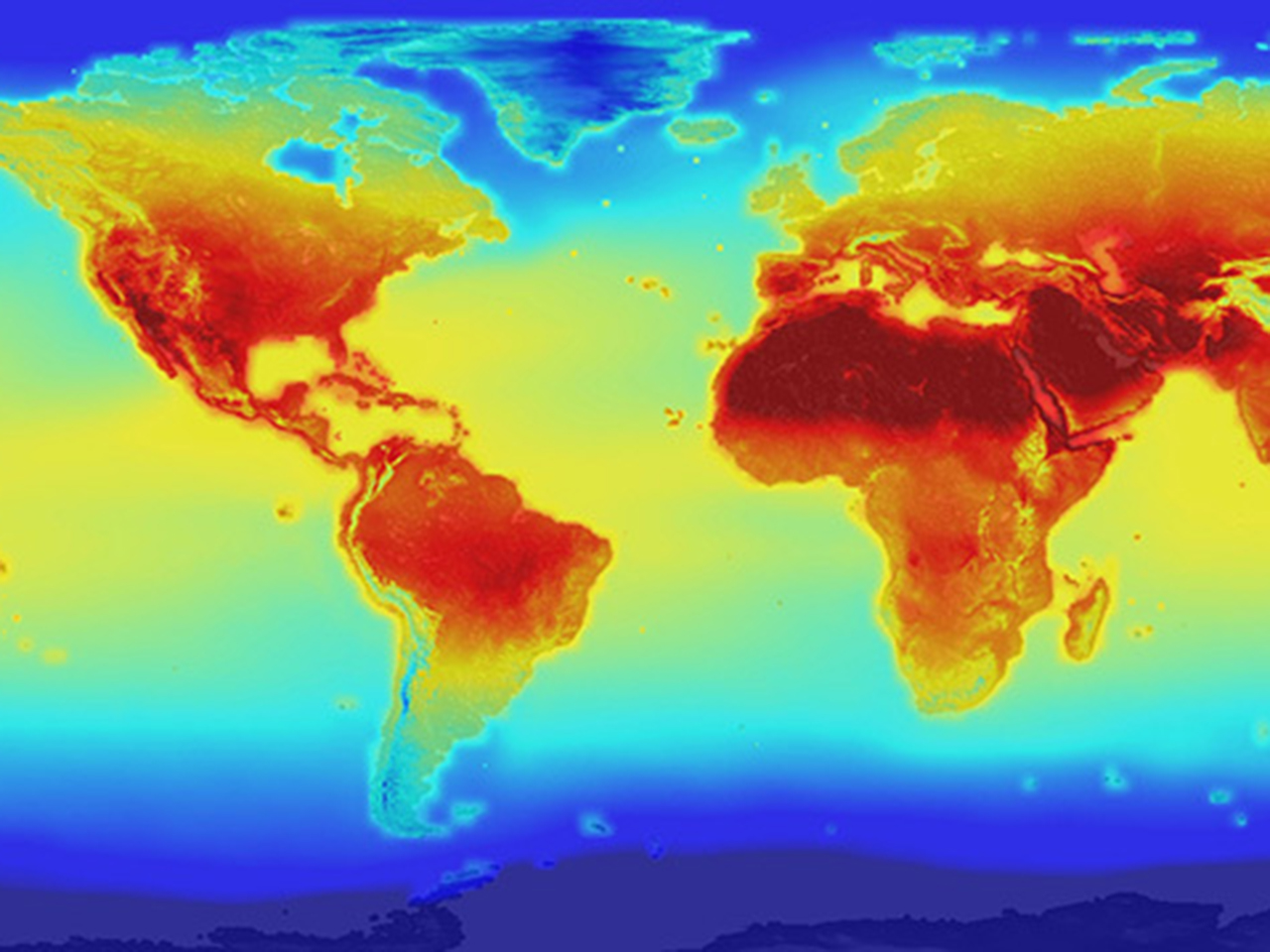

Even though climate change does not directly cause wildfires, climate change exacerbates environmental conditions that make wildfires more frequent and intense. Climate change can drive higher temperatures, more severe droughts, gustier winds, drier soil and weaker trees. All of these factors contribute to worsening wildfires.

Higher temperatures from climate change give rise to a positive feedback cycle. This cycle is a self-reinforcing effect where hot temperatures lead to extreme weather and droughts. Droughts can set the stage for wildfires, which create air pollution and smoke. The carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere from the air pollution and smoke lead to even higher temperatures, starting the cycle again.

"The changing climate is absolutely having an impact on how fires are burning, how they're spreading," said CAL FIRE Director Ken Pimlott in a video from the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center. "California historically has experienced large, devastating fires. What's really changing is the intensity of the fires, the duration of the fires, and certainly the frequency."

In addition to climate change, other factors — like fuel loads, the amount of flammable material in an area — are at play in exacerbating wildfires.

"Extreme weather conditions are certainly playing a role, but climate change isn’t driving all the change we’re seeing,” said UC Davis Forest Ecologist Hugh Safford when discussing California’s wildfire season in 2020. “Fuel loads played a major role in driving fire severity patterns in forested landscapes in 2020, like in other years. High fuel loads are due mostly to human management decisions over the last century or more, and we can do something about this issue."

3. What starts most wildfires?

There are some natural causes of wildfires, like lightning, but humans start about 85% of wildfires.

According to the National Interagency Fire Center, here are some of the ways people start wildfires:

- Arson

- Debris and open burning

- Equipment and vehicle use

- Firearms and explosives use

- Fireworks

- Misuse of fire by minors

- Power generation/transmission/distribution

- Railroad operations and maintenance

- Recreation and ceremony

- Smoking

- Anything that causes a spark

In an episode of UC Davis' Unfold podcast, Forest Ecologist and UC Davis Associate Professor of Plant Sciences Malcolm North discusses the importance of climate when it comes to wildfires.

North explains that a hotter, drier climate mixed with high-density forests creates the perfect environment for wildfires to start.

For the past several decades, wildfire management consisted of fire suppression systems — the effort to extinguish, control and prevent fires. People were fighting fires so frequently that forests became too dense.

Climate change’s high temperatures can kill trees, and so can bark beetles. These insects killed more than 130 million trees in California. These dead trees serve as fuel for wildfires.

Wildfires in high-density forests are harder to control, especially when the trees are dead and easily combustible.

4. What state has the most wildfires?

California is home to some of the largest and most destructive wildfires in the United States. While 2022 was a relatively mild wildfire season, the state experienced more fires and acres burned than any other state in the nation in 2021.

Millions of Californians live in places with a high or extremely high risk of wildfire, and that number is expected to increase. This increased risk is why researchers at UC Davis are working on solutions like building houses that don’t burn.

5. Are wildfires getting worse?

Yes. In California, the intensity, duration and frequency of wildfires are getting worse with time due to exacerbated environmental conditions from the effects of climate change and a rise in forest density.

California has experienced its worst fires within the past decade. The Camp Fire in 2018 was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history and came just a little over a year after the devastating Tubbs Fire.

Fortunately, researchers at UC Davis are working with local, state, federal and community groups to mitigate California’s wildfire crisis.

6. How does wildfire smoke affect humans and wildlife?

UC Davis animal science researchers studied the effects of wildfire smoke on animals. Their research sheds light on how wildfire smoke can affect humans, too.

Brain development issues in monkeys

During the 2018 Camp Fire, rhesus macaque monkeys housed outdoors at UC Davis’ California National Primate Research Center were unintentionally exposed to wildfire smoke. Studies show that the baby monkeys exposed to the smoke while in the womb were born with brain development issues.

When the baby monkeys were assessed, UC Davis researchers found increases in a marker of inflammation, a reduced cortisol response to stress, memory deficits and a more passive temperament than other animals.

Researchers believe wildfire smoke could affect unborn human babies in similar ways. They are starting new studies on humans to find out for sure.

Lung issues in monkeys and humans

What UC Davis researchers do know is that wildfire smoke can hurt primate and human lungs.

In 2008, CNPRC’s rhesus macaque monkeys also experienced natural smoke exposure. They showed similarities to the human inflammatory lung disease Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder.

After the Sonoma and Napa fires in 2017, UC Davis researchers surveyed the health of people affected by the fires. More than half of survey respondents reported experiencing symptoms like cough and eye irritation. Over 20% reported asthma or wheezing.

Heart issues in cats

At UC Davis’ Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, researchers studied cats that had been exposed to wildfire smoke from the 2017 Tubbs Fire and the 2018 Camp Fire.

Catherine Gunther-Harrington, assistant professor of clinical cardiology at UC Davis VMTH, was the lead author of the study.

More than half of the 51 cats studied had heart muscle thickening. About 30% of the cats had blood clots or were at high risk for developing blood clots. Six of the cats died due to heart issues.

“We also know that these cats inhaled smoke in a very urban environment, exposing them to toxicants,” said Gunther-Harrington. “These cats could be the canary in the coal mine, letting us know what might happen if more people are exposed to these types of wildfires.”

7. Can wildfires be good for the environment?

Yes! With our current high-density, unhealthy forests, wildfires are a clear crisis. But wildfires are actually good for the environment when managed well. In fact, controlled low-intensity fires are extremely important to maintain healthy, resilient forests and ecosystems.

For thousands of years, Indigenous Americans have conducted cultural burns, using fire as a way to restore the land. Non-Native fire ecologists, managers and community groups are increasingly learning from these practices to better manage today’s forests.

Meanwhile, state officials in California have created a shared stewardship agreement with the U.S. Forest Service to reduce wildfire risks on 500,000 acres of forest land per year.

So UC Davis alumni and researchers have teamed up to teach half a million landowners to burn 1 acre of their land through prescribed burns, in which low-severity fires are conducted on properties to reduce the threat of wildfire.

8. Can wildfires be prevented or prepared for?

Every year, wildfires take away human and animal lives and destroy homes and thousands of acres of land. People are mobilizing at the local, state and federal levels to prevent further wildfire devastation. UC Davis research is informing actions on the ground to help prevent, prepare for and adapt to wildfires.

Learn how to prevent and prepare for wildfires