Although the sense of smell has long been marginalized in the Western aesthetic tradition, contemporary artists have been experimenting with olfactory materials that act on breathers on a visceral level, entering and biochemically transforming their bodies, minds and moods. This was the subject of a talk, both online and live, as part of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art's Art Matters series on July 7.

Hsuan L. Hsu, professor of English at UC Davis, explored "Olfactory Ecologies and Contemporary Art."

Hsu's talk considered three ways of framing scent as a medium of environmental knowledge and intimacy: As a vehicle for communicating environmental toxicity; as an intoxicating and intimate form of human and more-than-human communication; and as a way of making public "smellscapes" more breathable and meaningful for people and communities whose olfactory experience has been attenuated by Western projects of deodorization and olfactory consumption.

Hsu opened with a discussion on the key characteristics of smell, including embodied, immersive, ephemeral, involuntary (decenters individual autonomy), ties to affect & emotion, subjective/culturally variable, difficult to describe in (English) words, biochemical, not-quite-conscious, and “trans-corporeal.”

Another concept that orients Hsu’s work is deodorization, described as the process of removing (most) smells from (some) public spaces through nuisance laws, deodorizing campaigns, and climate control, as well as the process of discrediting the sense of smell as a rich and diverse mode of experience and knowledge.

Hsu first studied embodied environmental knowledge through artwork by Boris Raux, Peter De Cupere and Sean Raspet.

Smell of a Stranger, by the well-known Belgian olfactory artist Peter De Cupere, uses smell to frame relations between the United States and Cuba. Reflecting on the Obama-era “Thaw” in U.S.-Cuba relations, de Cupere genetically modified nine local Cuban flowers and plants genetically modified to emit the scents of new American dollars, blood, sperm, vagina, dead body, gun powder, sweat, air pollution and geraniums.

“By incongruously pairing beautiful local plants with smells associated with sex tourism, labor exploitation, military violence, and pollution, De Cupere suggests that the opening of US-Cuba trade and diplomacy under the Obama administration could have a range of harmful effects upon Cuba’s people, culture, and environment,” noted Hsu.

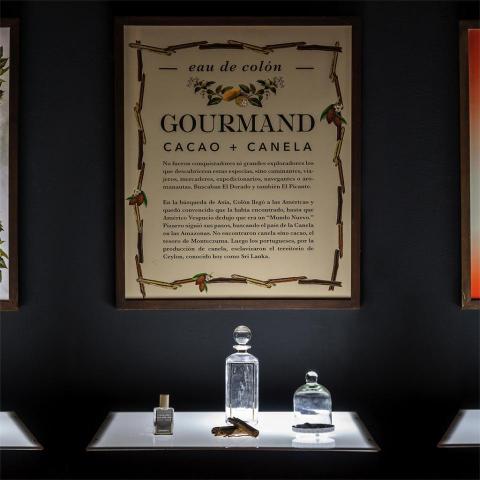

Hsu then explored olfactory modes of racism and colonialism through works by Beatrice Glow and Anicka Yi.

While sampling perfumes that feature scents such as cloves, nutmeg, peppercorns, tobacco, sugar, cinnamon, and cacao, visitors of Glow’s perfume bottles learned about the conditions of colonial violence and racialized labor that have made these plants available for consumption. While most of the scents were “pleasant,” Glow notes that “El Picante (nutmeg and cloves) and Oro Negro (black pepper) were not dialed down at all and people were often taken aback as those notes can be harsh." Similarly, “Blanc: Le Colonial was nauseatingly sweet with sugary and milky synthetic fragrance mixed in with vanilla reinforced by tonka beans. It’s an overdose of sweetness.”

“The discomfort induced by these scents interrupts the easy consumption of fragrance commodities, pairing the uncomfortable historical information Glow presents with unsettling sensory experiences,” commented Hsu.

Finally, Hsu explored materially redressing olfactory racism and colonialism through works by Renée Stout and Tanaïs.

“Environmental justice scholars and activists have long noted that capitalism exposes Black and other racialized communities to disproportionate environmental risks. Recently, scholars have framed environmental racism explicitly in atmospheric terms. But even when surrounded by racist atmospheres like those of the slave ship, factory, toxic neighborhood, tenement, or prison cell, Black people have produced powerful ‘microclimates’ supportive of Black breath and life.”

“I want to shift to work that leverages smell to produce supportive ‘microclimates,’ and to materially counteract processes of environmental racism,” said Hsu.

In addition, in their Memory as Living Art (MALA) podcast and perfume project, the Bangladeshi-American writer and perfumer Tanaïs creates perfumes intended to support the memories and well-being of Black women whose sensory experience had been deprived by years spent in alternately deodorized and noxious carceral spaces.

“Here, perfume isn’t an escape from reality or a prestige commodity — it reintegrates Black women’s memories and heritage that have been eroded by the prison’s interruptions of time, place, community, and sensory experience.”

Hsu concluded that these observations provide critical perspective on the uneven risks associated with deodorization and air pollution, and on various forms of olfactory racism.

“Olfactory practices of intimacy and anti-racist care through the creation of ‘microclimates’ [are] supportive of BIPOC lives,” Hsu said.

Media Resources

Media contact:

- Karen Nikos-Rose, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu