Scientists found plastic debris in the digestive tract of a southern right whale stranded in Argentina, according to a study from the Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program, co-led by the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine; and Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas in Argentina.

The study, published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, is the first finding of macroplastic debris recorded in this species.

The juvenile male whale was found dead on the shores of Golfo Nuevo off Península Valdés in Argentina in 2014. The site is a major breeding ground for southern right whales and a UNESCO World Heritage site for its conservation of marine and terrestrial wildlife.

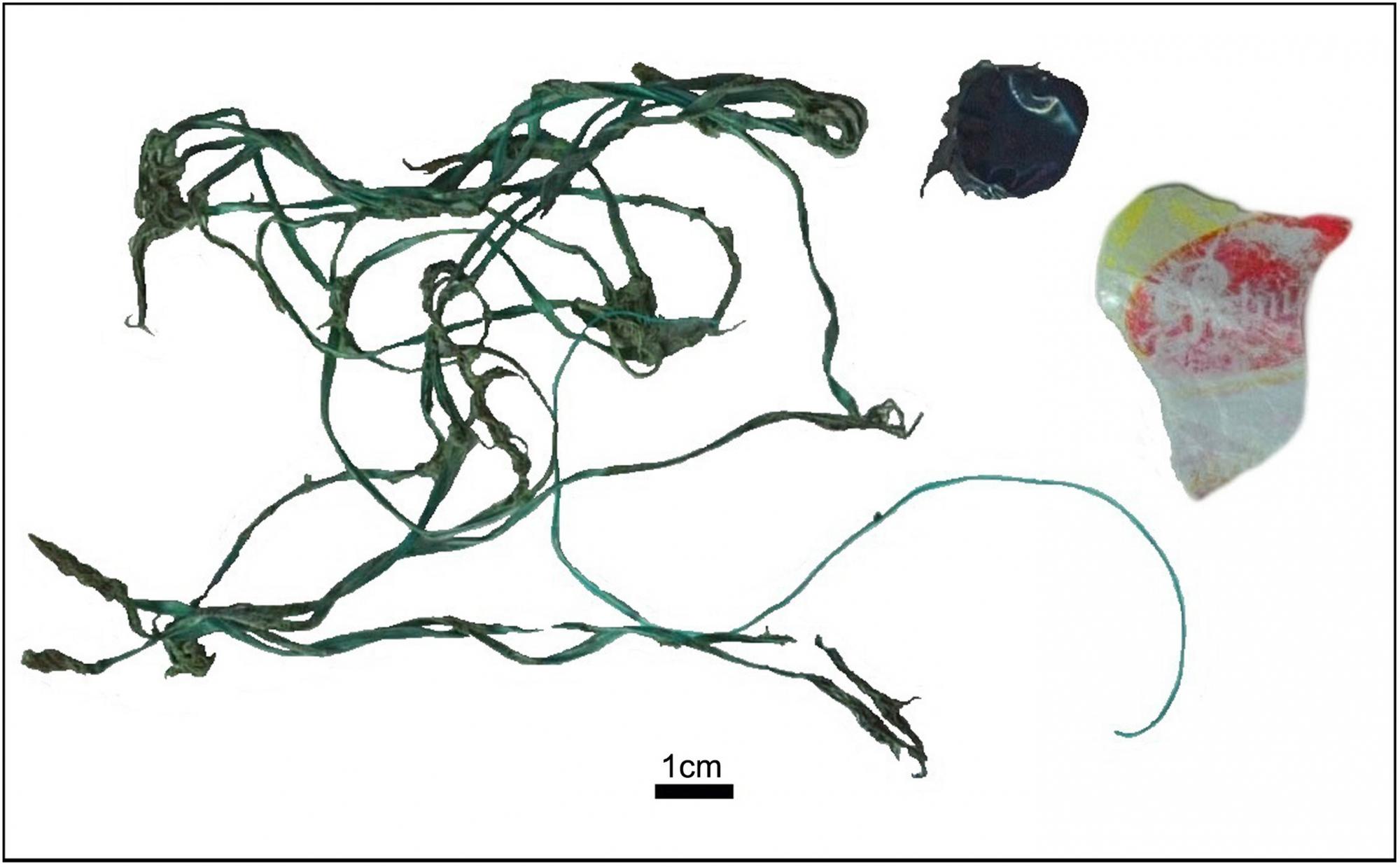

Scientists examined the whale’s intestinal contents and found nylon rope and plastic wrappers. While the necropsy indicates the whale likely did not die from ingesting this plastic, the study said the finding points to the broad reach of plastics in the ocean.

“This is the first record of litter ingestion in southern right whales, and we sadly suspect it will not be the last,” said lead author Lucia Alzugaray from the Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program. “For decades, we have witnessed how our litter affects hundreds of marine species and disrupts ecosystems. It is time to understand that the health and welfare of all species, including our own, depends upon a healthy environment.”

A plastic planetary crisis

Plastic pollution is considered a planetary crisis by the U.N. Environment Program. Humans produce more than 300 million metric tons of plastic a year. A significant portion of that ends up in the ocean. At this rate, the ocean would hold more pounds of plastic than fish by 2050.

Scientists have documented more than 800 marine species affected by plastics, including all species of sea turtles, more than 40 percent of whales and dolphins, and 44 percent of seabirds, said co-author Marcela Uhart of the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine’s Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, Latin America program.

“This study hits the nail on the head that these are the things we’re doing to our planet and these are among the species we’re putting at risk,” said Uhart, who also co-directs and founded the Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program in 2003. The program works to identify health risks for whales by examining those that die in Península Valdés.

‘We cannot point our finger’

“While the north Atlantic right whale is on a route to extinction, southern right whales are considered an example of hope,” said Mariano Sironi, who co-directs the Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program with Uhart and is the scientific director of Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas in Argentina. “Southern right whales were nearly exterminated by commercial whaling before the practice was banned in the 1930s. They’ve been slowly recovering since and are now categorized as a species ‘of least concern’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.”

Southern right whales migrate annually to the Península Valdés breeding ground in Argentina after spending the summer months feeding in nutrient-rich areas of the South Atlantic and in sub-Antarctic waters. By the end of winter and an extended fasting period, they are often hungry. Filter feeders, they skim the ocean’s surface, gulping water they strain through the baleen to ingest zooplankton, such as copepods and krill, their main food source.

When the scientists found the juvenile whale, its state of digestion indicated it likely ate the plastic while at Península Valdés.

“We cannot point our finger and say, ‘This whale ate this somewhere in the ocean,” Uhart said. “It ate it right here, in a natural reserve, where we should be protecting them. It is actually our fault that this whale found those items in the ocean and ate them. We hope this study increases awareness of the plastic crisis and how it is linked to what we do every single day.”

The study was funded by the Island Foundation, UC Davis and the Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas.

Media Resources

Marcela Uhart, UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, muhart@ucdavis.edu

Lucia Alzugaray, Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program, luciaalzugarayg@gmail.com

Mariano Sironi, Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, mariano.sironi@icb.org.ar

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu